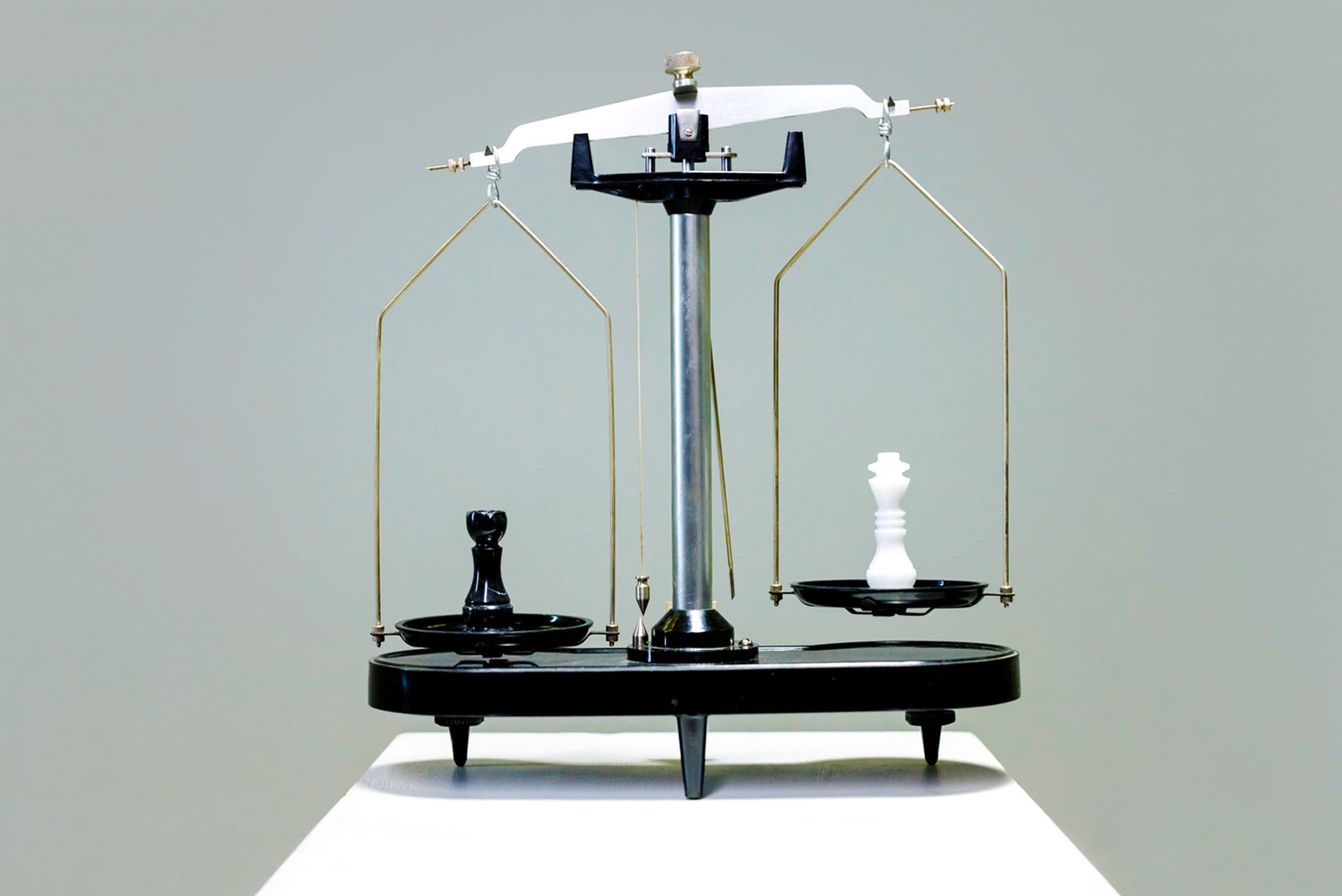

Open Access: Is It Fostering Epistemic Injustice?

A romantic notion of Open Access is that once all knowledge is free, the injustice in the world caused by the knowledge advantage of some will be eliminated. But what if that doesn't happen and OA actually reinforces existing patterns of inequality? In the guest article, Nicki Lisa Cole and Thomas Klebel share their findings from the ON-MERRIT project.

by Nicki Lisa Cole and Thomas Klebel

One of the key aims of Open Science is to foster equity with transparent, participatory and collaborative processes and by providing access to research materials and outputs. Yet, the academic context in which Open Science operates is unequal. For example, core-periphery dynamics are present, with researchers from the global north dominating authorship and collaborative research networks. Sexism is present, with women experiencing underrepresentation within academia (see also) and especially within senior career positions (PDF); and racism manifests within academia, with white people being over-represented among higher education faculty. Inequality is the water in which we swim, therefore we cannot be naive about the promises of Open Science.

In light of this reality, the ON-MERRIT project set out to investigate whether Open Science policies actually worsen existing inequalities by creating cumulative advantage for already privileged actors. We investigated this question within the contexts of academia, industry and policy. We found that, indeed, some manifestations of Open Science are fostering cumulative advantage and disadvantage in a variety of ways, including epistemic injustice.

Miranda Fricker defines epistemic injustice in two ways. She explains that testimonial injustice “occurs when prejudice causes a hearer to give a deflated level of credibility to a speaker’s word,” while hermeneutical injustice “occurs at a prior stage, when a gap in collective interpretive resources puts someone at an unfair disadvantage when it comes to making sense of their social experiences”. Here, we take a look at ways in which Open Access (OA) publishing, as it currently operates, is fostering both kinds of epistemic injustice.

APCs and the stratification of OA publishing

Research shows that article processing charges (APCs) lead to unequal opportunities for researchers to participate in Open Access publishing. The likelihood of US researchers publishing OA, especially when APCs are involved, is higher for male researchers from prestigious institutions, having received federal grant funding. Similarly, APCs are associated with lower geographic diversity of authors within journals, suggesting that they act as a barrier for researchers from the Global South, in particular. In our own research, specifically investigating the role of institutional resources, we found that authors from well-resourced institutions both publish and cite more Open Access literature, and in particular, publish in journals with higher APCs than authors from less-resourced institutions. Disparities in policies that promote and fund OA publication is likely a significant driver of these trends.

While these policies are obviously helpful to those who benefit from them, they are reproducing existing structural inequalities within academia, by fuelling cumulative advantages of already privileged actors, and further side-lining the voices of those with fewer resources. This form of testimonial injustice is historically rooted and widespread within academia, with research from the Global South often deemed less relevant and less credible (see also). With the rise of APC-based Open Access, actors with fewer resources face additional barriers to contributing to the most recognised outlets hosting scientific knowledge, since journal prestige and APC amounts have been found to be moderately correlated. Given that scientific research is expected to aid in tackling urgent societal challenges, it is alarming that current trends in scholarly communications are exacerbating the marginalisation of research and knowledge from the Global South and from less-resourced scholars more generally.

Access Isn’t Enough

One of the arguments in support of Open Access is that it fosters greater scientific use by societal actors. This is a commonly cited refrain in the literature, but we found that OA has virtually no impact in this way. Rather, we heard from policy-makers that they rely on existing personal relationships with researchers and other experts when they seek expert advice. Moreover, we heard from researchers that it is far more important that scientific outputs be cognitively accessible, or understandable, when disseminating research to lay audiences.

Communicating scientific results to lay audiences requires time, resources, and a particular skill set, and failing to account for this reality limits the pool of actors able to do it (to those already well-resourced and ‘at the table’) and inhibits the potential for science to impact policy-making and to be useful to impacted communities. In this way, Open Access absent understandability creates hermeneutical injustice among any population that would benefit from understanding research and how it impacts their lives, but especially among those who are marginalised, who may have participated in research or been the subjects of study, and to whom the outcomes of research could provide a direct benefit. People cannot advocate for their rights and for their communities if they are not provided with the tools to understand social, environmental and economic problems and possible solutions. In this way, the concept of Open Access must go beyond removing a paywall to readership and provide understandability, aligning with the “right to research”, as articulated by Arjun Appadurai.

What We Can Do About It

In response to these and other equity issues within Open Science, the ON-MERRIT team worked with a diverse stakeholder community from across the EU and beyond to co-create actionable recommendations aimed at funders, leaders of research institutions, and researchers. We produced and published 30 consensus-based recommendations, and here we spotlight a few that can respond to epistemic injustice and that may be actionable by libraries.

- Supporting alternative, more inclusive publishing models without author-facing charges and the use of sustainable, shared and Open Source publishing infrastructure could help to ameliorate the inequitable stratification of Open Access publishing.

- Supporting researchers to create more open and understandable outputs, including in local languages when appropriate, could help to ameliorate the hermeneutical injustice that results from the inaccessibility of academic language. In conjunction, supporting partnerships with other societal actors in the translation and dissemination of understandable research findings could also help to achieve this.

- We believe that librarians could be especially helpful by supporting (open and sustainable) infrastructure that enables the findability and understandability of research by lay audiences.

Visit our project website to learn more about ON-MERRIT and our results, and click here to read our full recommendations briefing.

This might also be interesting for you:

- Mitigating risks of cumulative advantage in the transition to Open Science (YouTube Video), Recording of the presentation given by Tony Ross-Hellauer at the Open Science Conference 2022

- Open Science Conference 2022: New Challenges at the Global Level

- Quick Guide to Open Access

- Podcast episode „New Models for the Publication Market“ (German)

- Podcast episode “Open Access and the Publication Market“ (German)

- Perspectives on Open Science and Inequity: Who is Left Behind?

- Open Access Barcamp 2022: Where the Community Met

- Open Access Survey in Greece: Status Quo, Surprising Findings and Starting Points

- Open Access in Finland: How an Open Repository Becomes a Full Service Open Publishing Platform

- Open Access Days 2021: Highlights and Most Interesting Topics

- Open Access Journals: Who is Afraid of 404?

- Science Checker: Open Access and Artificial Intelligence Help Verify Claims

- Third-Party Material in Open Access Monographs: How Far-Reaching is the Creative Commons Licence Really?

- Open Access for Monographs: Small Steps Along a Difficult Path

Nicki Lisa Cole, PhD is a Senior Researcher at Know-Center and a member of the Open and Reproducible Research Group. She is a sociologist with a research focus on issues of equity in the transition to Open and Responsible Research and Innovation. She was a contributor across multiple work packages within ON-MERRIT. You can find her on ORCID, ResearchGate and LinkedIn.

Portrait: Nicki Lisa Cole: Copyright private, Photographer: Thomas Klebel

Thomas Klebel, MA is a member of the Open and Reproducible Research Group and a Researcher at Know-Center. He is a sociologist with a research focus on scholarly communication and reproducible research. He was project manager of ON-MERRIT, as well as investigating Open Access publishing, and opinions and policies on promotion, review and tenure. You can find him on Twitter, ORCID and LinkedIn.

Portrait: Thomas Klebel: Copyright private, Photographer: Stefan Reichmann

View Comments

Open Science & Libraries 2022: 22 Tips for Conferences, Barcamps & Co. – Part 2

Which conferences and events might be worth a (online) visit in the 2nd half of 2022?...