Open Science Right from the Start: How the UBC Okanagan Library Introduces Students to Good Scientific Practice

Students have always been catalysts of change. Why not use this characteristic for the cultural change towards more open science at universities? This is exactly what the UBC Okanagan Library in Canada is doing, and it is addressing first-year students with a unique pilot project with special Open Science modules.

we were talking with Sharon Hanna, Jason Pither and Mathew Vis-Dunbar

The two-year strategic project of the UBC Okanagan Library at the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Canada aims to teach Open Science practices as early as possible in the early stages of study, so that students can benefit from them throughout their academic careers. The modules developed specifically for this purpose and anchored in the curriculum include the creation, deployment and evaluation of a comprehensive learning and teaching programme to promote the information literacy (IL) of students in the field of Open Science. Sharon Hanna, Jason Pither and Mathew Vis-Dunbar have been involved in the project and tell us today how they are working to change the university incentive system, why it is so essential to teach Open Science practices to undergraduates, and the role libraries play in this.

Why is it so important to introduce open science to students as early as possible in their university careers?

It has numerous benefits, both for the prospective researchers and for the entire undergraduate population:

- Our qualitative experience is that students feel empowered by the early Open Science training, and therefore show greater interest and engagement when presented, for example, with case studies or primary research articles. We’re hopeful that this applies more broadly, outside the classroom, where students need to make informed decisions as active members of society.

- Values and practices that are introduced early can be more fully developed and reinforced throughout the undergraduate curriculum, and this in turn increases the likelihood that the practices become habits. This is especially beneficial to students who aim to pursue science careers. Crucially, we’ve seen how these habits can propagate up through labs to principal investigators, and ultimately precipitate wholesale changes to research workflows.

- By their final year, students will be well equipped to apply Open Science best practices to research endeavours such as honours research projects and capstone projects. We therefore anticipate substantive improvements in the quality of undergraduate-led research.

What is your open science library information literacy programme for undergraduates about?

Our programme aims to provide templates and resources to enable instructors to weave open science principles and practices into the existing curriculum in such a way that Open practices become as automatic to students as putting on a lab coat. Put simply, Open Science is better science.

Those who have a serious interest in careers in the sciences or allied fields (for instance health professions and environmental protection) have shown an interest in knowledge that will increase the quality of their scientific work. Among Open Science module templates that have been implemented or are in the queue for development are:

- reproducible analysis and literate programming,

- research data management,

- digitisation of lab books and field notes,

- use of Open Data collections,

- peer review,

- advanced Questionable Research Practices (QRP)-prevention and

- use of alternative measures of impact.

Why should undergraduate students participate in your programme?

First of all, Open Science content counts for a percentage of the students’ grade in participating courses. Raising grades is always a good incentive! Second, students will have the opportunity to learn about open practices that increase the transparency and accessibility of science and are increasingly being demanded by funders and employers. Third, Open Science is better science, period. Finally, students have shown marked idealism and appreciation for having learned, simply in their capacity as world citizens, about the ideals of Open Science (an intrinsic reward!).

How can universities with limited resources find ways to introduce incentives and rewards for the knowledge and practice of open science among students?

For instance, grading schemes for laboratory reports can reward transparency and openness — about procedural mistakes and mishaps, for example — alongside reward for correct answers.

With respect to undergraduate-led research opportunities, existing scholarships and honours thesis applications can be tailored to indicate preference for proposals that include plans for Open Science best practices. If resources exist, top-ups can be provided that enable, for example, publishing in open access journals. More generally, our ultimate goal is to provide accreditation for successfully completing a full regimen of Open Science training at the undergraduate level. We’re confident that this type of accreditation will grow rapidly in value, as employers in both the private and public sectors seek out graduates with formal Open Science training.

How does your library contribute to the programme?

The UBC Okanagan Library has been a key player in securing financial supports to enable us to run this initiative.

Our Open Science librarian consults with instructors and lab managers interested in introducing Open Science principles and practices into the classrooms and labs, and contributes to the development of learning resources and objects.

What part should libraries generally play and what is their key role when helping to establish open science with undergraduates?

Libraries form an interesting junction point in the research life cycle. Traditionally the realm of monographs and serials, the kind of content that needs to be organised and made discoverable to enable research has grown over the years to include a host of academic outputs, such as protocols, preprints, data, and code.

While libraries don’t necessarily host all of these outputs, libraries and librarians provide the systems that connect them. In this role of both acquisition and connection of research inputs and outputs, libraries also play a critical support and educational role in information literacy: the degree to which we understand how information is produced, disseminated, and digested impacts the trust that we can put in any given piece of evidence.

What are the key learnings you have gained so far after implementing your programme for the first time in 2019/2020?

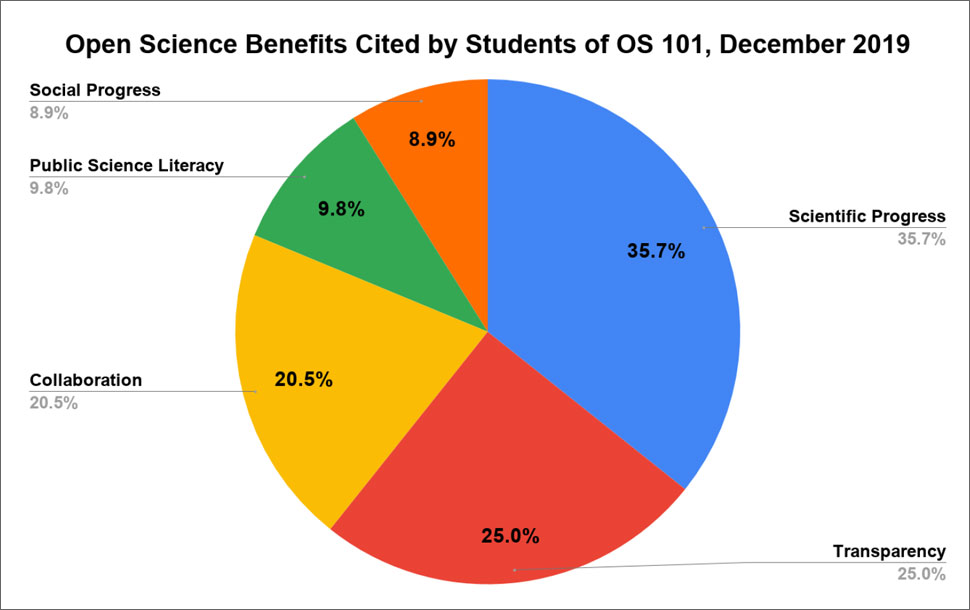

First-year Biology students “test-drove” our introductory modules in 2019/2020. The students showed a keen interest in Open Science principles and professed changed attitudes in favour of Open Science practices by the end of the course. Many students also responded favourably, but also expressed a desire to see material with greater relevance to their studies.

This summer and fall, we’ll be working with the Biology Lab Coordinator to integrate the introductory modules more closely with the curriculum and to introduce lab exercises that specifically link to the content. Lab teaching assistants will also receive an Open Science orientation. Open Science will make up a larger portion of a student’s course marks.

In addition our role in Open Science instruction is changing from creating content to one of providing templates, resources, and consulting advice to instructors.

What can other universities and libraries in particular learn from your programme? Can they reuse your material?

One of the big takeaways that we’ve had is the value of undertaking this as a joint initiative with support from faculty, the library, the Provost’s office, our Advanced Research Computing department, and the Strategic Initiatives and Planning office at University of British Columbia. Lacking this support from any one of these bodies would have made our efforts much more challenging.

In terms of re-use of materials, this is very much a living project, still strictly in its pilot phase. In the interest of promoting sharing, collaborating, and openness generally, it is our intention to have all of our materials made available through a CC licence. At the moment, most of our content has not been formally released outside of the classrooms at UBC Okanagan Campus. But anyone interested in what we’re doing can certainly reach out and we’d be happy to talk. And, as aspects of our work are released, they will be found on our website.

Sharon Hanna is Open Science Librarian at the UBC Okanagan Library, Kelowna, Canada. She is responsible for undergraduate Open Science instruction; support for blended learning design interns; technical aspects of archives digitisation projects; and subject liaison in quantitative sciences and languages.

Dr Jason Pither is Associate Professor in Biology at the UBC Okanagan Campus. He is an ecologist and principal investigator in the Biodiversity and Landscape Ecology Research Facility at UBC’s Okanagan campus. Since 2016, Dr Pither has been collaborating with members of both UBC campuses (Vancouver and Okanagan) to build capacity around training and support of best practices in Open Science.

Mathew Vis-Dunbar is the Southern Medical Program Librarian at the UBC Okanagan Campus. He supports researchers across the sciences to engage in open, transparent and reproducible research.

The copyright of the photos of the interview partners belongs to the UBC Campus.

View Comments

FIT4RRI: Shaping Open Research and Innovation Responsibly

The Open Science and the Responsible Research & Innovation (RRI) movements are...