Open Science Conference 2021: On the Way to the “New Normal”

What were the main points of focus at the Open Science Conference 2021? What are the topics currently most affecting the community? From which best practice examples can we learn the most? Today we take a look back at the pure digital #OSC2021.

by Guido Scherp and Claudia Sittner

The Open Science Conference 2020 (#OSC2020) was more or less the last attended event that could take place before the corona pandemic arrived in Europe. Since then, numerous events have been transferred to the digital sphere. These include the Open Science Conference 2021 (#OSC2021), which was able to reach out online to almost 400 Open Science experts and enthusiasts from 33 countries.

[Copyright: ZBW]

One thing is clear, however: The Open Science community is growing and becoming increasingly professional on all levels, with different stakeholders and in various aspects of Open Science. Important grassroots movements continue to play a role in giving impetus, pushing forward the required transformation, and initiating change. In his capacity as chairperson of the conference, Klaus Tochtermann emphasised that Open Science was on a good path towards the “new normal” of science and that development is taking place at a very rapid pace. In this retrospective, we look back at the current major challenges and developments of this wide range of topics in the community.

#OSC2021 – First virtual Open Science Conference

This year the conference features diverse presentations, a panel discussion on the effects of the corona pandemic on open practices and a virtual poster session with 17 posters. The event was presented by the science journalist David Patrician, who was always in the mood for a chat and never seemed to get tired of giving the speakers a hearty round of virtual applause. In one lunchtime break there was a poster session in which the participants gained an insight into the diverse projects and activities that are driving forward the practice of Open Science. There were also two “meet the speakers” sessions to encourage a little more interaction and exchange between speakers and participants.

Questions on the presentations and for the panel session could be submitted via a kind of chat function, which was used intensively by the listeners, as was the option to vote up particularly interesting questions. The high number of questions submitted was probably also influenced by the fact that submitting a question in writing [rather than orally] is fundamentally less inhibiting, and that it was also possible to ask the question anonymously. Questions from the participants were incorporated into the panel discussion in particular.

Transferring a conference such as this into the digital sphere is a complex challenge, not only for the organisers but also for the contributors and participants. After a year of the pandemic, experiences have definitely been made and people have increasingly got used to the digital environment. But there are many different providers, and often one has to come to grips with a completely new platform. A special note of thanks therefore goes to all the contributors and also the participants for their willingness to do this. And if, in earlier times, one had to hope that the infrastructure for travelling to the conference venue would work perfectly, nowadays one needs to hope that the digital infrastructure remains stable. A snowstorm in the southern USA had an effect on our programme because speaker Lilly Winfree (Open Knowledge Foundation, USA, Great Britain) was unable to give her presentation as planned owing to a power cut. The presentation was subsequently recorded and made available – an advantage of the digital format.

Open Science for all: Opening science up

One important aspect of Open Science is inclusion, meaning the opening up of science to societal stakeholders and involving them in the process. An important actor in this field is UNESCO, which is aiming to ratify the “UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science” by the end of 2021. The general aim of the recommendation is to create a global consensus on the topic of Open Science, but also to recommend concrete measures, such as in the fields of Open Access and Open Data. This is underpinned by a highly participative process incorporating all stakeholders.

Ana Persic (UNESCO, France) gave in her presentation “Building a Global Consensus on Open Science – the future UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science” an overview of the current status of the recommendation (first draft), thereby addressing further interesting aspects on the background to the issue. When it’s about closing the gaps between the different world regions relating to science, technology and innovation, Open Science has the potential to be a game-changer. It’s therefore an important aspect of the UNESCO recommendation that Open Science also means that worldwide everyone has equal access to Open Science and can profit from it equally. Hence it is important to enter into a corresponding dialogue, with the so-called global south, for example, in order to address financial and technological disadvantages but also to involve indigenous peoples and/or incorporate indigenous knowledge.

Although the recommendation will not be formally binding, a monitoring process will definitely take place and member states must report on the implementation status. Scholarly communication plays a larger part in the new draft version, and the role of Open Science in the context of sustainable development goals is more closely addressed.

The topic of the opening of science to societal stakeholders was also covered in further presentations. The field of “citizen science / community science” explores, for example, how civil society can be integrated more closely in science. The “Sustainable Futures Academy” offers a platform through which researchers can discuss the challenges and opportunities of a sustainable future together with different people from society in a cross-disciplinary context.

Alina Loth (Berlin School of Public Engagement and Open Science, Germany) reported in her presentation “Digital collaborations as an opportunity to strengthen engagement between various stakeholders internationally – the Sustainable Futures Academy” on the experiences and advantages offered by moving this originally planned presence event into the digital sphere. Her conclusion: There is always an interplay of challenges and opportunities, and each topic/project needs its own set of digital tools to support it.

It’s also important to develop trust with the target group in the digital sphere too, according to Loth. Ultimately however, digital tools offer a further possibility of opening up the “ivory tower” of science and enabling fair exchange of knowledge – and doing this independent of location & time, and from a very international perspective. Thus one central lesson learned from the project is to use hybrid or purely digital formats alongside face-to-face events. The collected experiences have been recorded in a video.

Community is growing: Opportunities to learn from another and exchange ideas

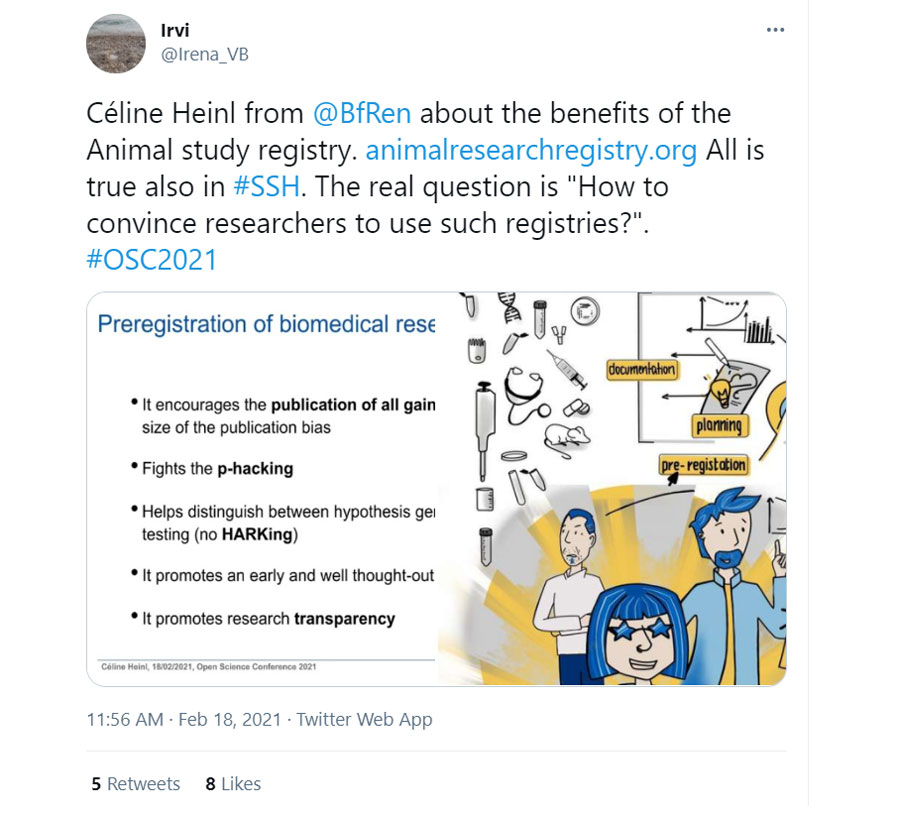

It’s possible to see how the community is growing in many of the presentations at the Open Science Conference. And it is also often emphasised that exchange between the communities is important for sharing experiences and best practices. Céline Heinl (German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, German) showed in her presentation “Preregistration – How to bring transparency into animal research”, her first presentation in an Open Science context, how we can all learn from other communities.

The community is aware of known problems such as non-published data from experiments involving animals or a publication bias through a focus on positive results. Alongside the double implementation of experiments and its associated wasting of resources as well as insufficient knowledge transfer from research results in clinical research, unnecessary experimentation on animals contradicts ethical principles. The “Animal Study Registry” for studies involving experimentation on animals was therefore started, based on biomedical research and its preregistration practice for clinical studies.

Planned studies can be registered there and then be linked at a later date to corresponding results, data and publications. According to Heinl, these can help – very much in the sense of Open Science – to improve the research quality through transparency and reproducibility, improving animal protection at the same time. This would allow to develop a more open and more positive way of dealing with mistakes, which could also significantly benefit future researchers. And this could also be adopted in scholarly communication, because the topic of experimentation on animals is always a delicate one among the public.

Best practices for a new academic incentive system

In the discussion about the challenges of the implementation and stronger entrenchment of Open Science in the scientific system, the topic of cultural change is usually addressed. One trigger to foster this change is the adjustment of the academic incentive and career system. The required indicators, however, are very complex, owing to the breadth of the Open Science activities depicted and the different levels to be considered (institution, discipline, individual researchers…). And there are nowadays a plethora of existing indicators.

To push the topic forward, the Research Data Alliance (RDA) has started the “Open Science Rewards and Incentives Registry”, which was introduced by Hilary Hanahoe (RDA, Italy, Great Britain) in her presentation on “Rewards and Incentives for Open Science: A global registry, a global collaboration”. The registry is a publicly accessible, searchable and evidence-based online platform that allows the recording of both intended projects and experiences already learned regarding changes in the reward and assessment system of science.

A community-based knowledge platform with best practice examples will ultimately develop that enables learning from each other and knowledge exchange, according to Hanahoe. Existing examples are the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA) and corresponding efforts in the Netherlands.

Hanahoe emphasises, however, that the registry is not a monitoring platform. The registry is a direct result of the recommendations of the EU Open Science Policy Platform (PDF, OSPP), which in its second phase focussed on rewards and incentives (“responsible metrics”) among other things.

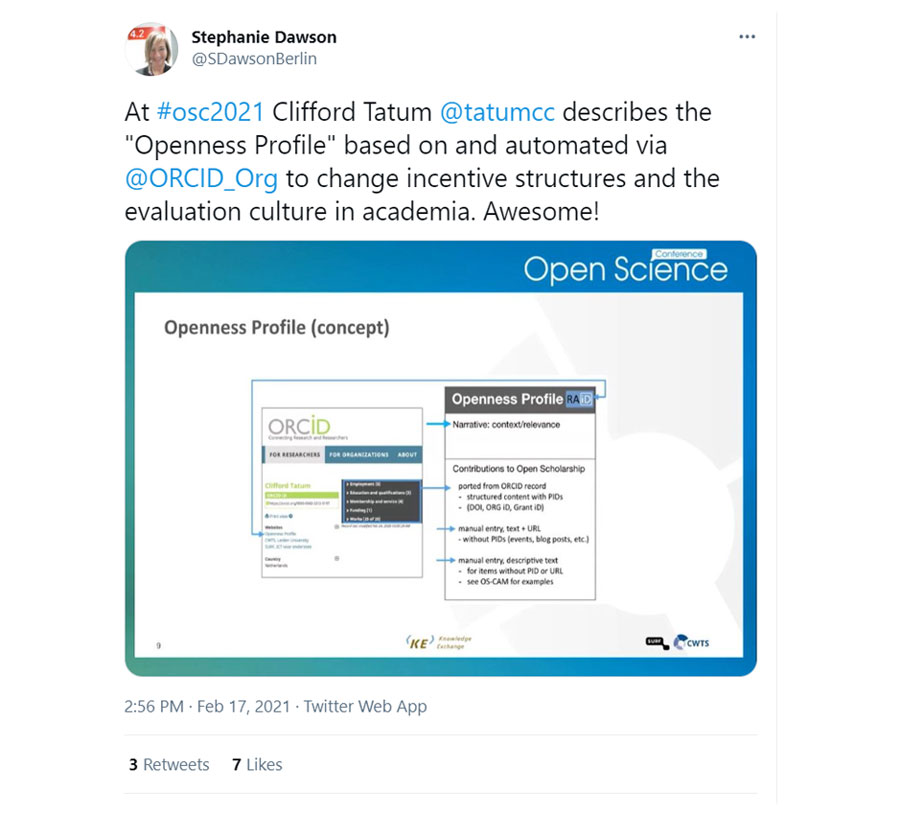

Clifford Tatum (Leiden University, Netherlands) gave a suitable example for the registry in his presentation “The puzzle of research evaluation: Opportunities and obstacles on the way to full Open Scholarship”, in which he introduced the concept of “Openness Profile”. In his presentation, Tatum also emphasised that the implementation of top-down-driven policies is dependent on a comprehensive cultural transformation in connection with an established recognition and reward system. For this transformation, however, bottom-up initiatives are also important. He has therefore designed the “Openness Profile” together with several colleagues, to create a connection between top-down policies and bottom-up implementation possibilities.

Technically, the profile uses the Research Activity ID (RAID) as a central container, as well as various persistent identifiers (PID), in order to record structured or unstructured different Open Science activities and link them to an ORCID profile. The desire for Open Science activities to be recognised is there, according to Tatum. This was also confirmed by interviews that took place in the context. Universities therefore play a key role and have the opportunity to force the cultural transformation. As yet, the “Openness Profile” is only a concept, but will be further discussed with the community in the form of a summit.

Sustainability and long-term financing

Having a digital infrastructure with respective platforms and tools but also support represents a substantial basis for the implementation of open practices. There has been plenty of movement and fluctuation on this issue in recent years, which has led to some lack of transparency. To support open practices sustainably, the infrastructure has to be sustainable too, something which Vanessa Proudman (SPARC Europe, Netherlands) pointed out in her presentation “In a locked-down-world: how can we continue to support Open Science to ensure immediate digital access to research to those who need it?”.

This remains a problem, because many initiatives start off project-based with temporary financing, but funding institutes would rather invest in innovation than in running costs. There is a danger that these initiatives would disappear or become commercialised and one fall into a situation of dependency. Not only development but also the running costs of Open Science infrastructures would consume resources. To raise the resources needed for permanent operations, sustainable financing models are required, which could differ substantially from each other.

Popular preprint servers such as arXiv, MedRxiv and BioRxiv lie in the hands of established research institutions, for example. Services such as the Directory of Open Access Journal (DOAJ) or CrossRef are based on memberships and sponsoring models. This incorporates the community in order to take account of their needs.

The latter is important, states Proudman, so that Open Science infrastructures lie in the hand of communities and are managed and sustained by them. And the infrastructures themselves need to be open, for example through the use of open standards and protocols. The Global Sustainability Coalition for Open Science Services (SCOSS) campaigns for the sustainability of Open Science infrastructures by creating a framework to bear the respective costs jointly.

Bottom-up impetus continues to be important

If you take a look at the last ten years, the Open Science movement has certainly had successes. Starting as a so-called “grassroots movement”, Open Science has reached the highest decision-making and organisational levels. Nevertheless, the bottom-up engagement of numerous volunteers continues to remain important in keeping the cultural transformation and implementation of open practices going and providing new impetus.

Leonhard Volz (Journal of European Psychology Students – JEPS, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands) introduced in his presentation “The Journal of European Psychology Students – A decade of student-organised scientific publishing as peer-education” a very clear example of exactly this, with his “Journal of European Psychology Students” (JEPS), and reports on his experiences.

The high fluctuation of the people working on the project, quality assurance and guaranteeing the sustainability of the Open Access infrastructure are particular challenges, according to Volz. Everyone working on JEPS is a volunteer. JEPS has continued to develop and taken up new requirements with research data for example. Ultimately, JEPS has become an Open Science point of contact for students and wants to continue and expand in its advocating of open practices.

And from bottom-up movements, communities can be created. Danielle Cooper (Ithaka S+R, USA) explored this in her presentation “Data Communities: Data Sharing from the Ground Up”. Data communities are formal or informal groups of scientists who share a specific kind of data with each other, independently of boundaries of academic discipline. They are often created bottom-up on the basis of a common interest and goal. The “Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data” (GISAID) is a best practice example of this, states Cooper.

Via GISAID, data concerning influenza viruses are shared; the platform has been supplemented to include corona virus data in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to Cooper, it is essential to understand data communities and the practices of data sharing, to discover developing data communities at an early stage and support them with technical and strategic advice on the topic of sustainability, for example.

To this end, the non-profit institution for whom she works, Ithaka S+R, is involved in corresponding qualitative studies concerning research practices which are also carried out with academic library partners. According to Cooper, there are three central characteristics of successful data communities:

- They are created bottom-up.

- They have developed community norms.

- Technical barriers have been mitigated.

Marte Sybil Kessler (German), (Stifterverband, Germany) gave in her presentation “Generation O – scaling open practices in Higher Education / How can we help ‘open-pioneers’, ‘-innovators’ and ‘-activists’ change the Higher Education System?” an insight into efforts to change the nature of the higher education system. For her, “Generation O” are the open pioneers, open innovators and open activists, and also, in principle, a kind of bottom-up movement. She shows how they find, in multidisciplinary teams and together with the innOsci Future Lab (German), “strategies, support structures and processes for the implementation and scaling of open practices in higher education and for strengthening Generation O”. Different prototypes have thereby been created from the Future Lab that explore the assessment and measurability of open practices and certified online courses, among other things.

The transformation in the higher education system towards more openness, however, is a “wicked problem” owing to its complexity and diverse dependencies. Progress is possible only through a comprehensive strengthening of open practices and the corresponding support to make these a powerful tool for making science and research accessible to all spheres of life. These activities are embedded in the Projekt innOsci, in which the general objective is to link Open Science and Open Innovation.

Open Science during the corona pandemic

During the #OSC2021 panel discussion on “Open Science in a Time of Global Crises” in particular, the influence of the corona pandemic on the worldwide development of Open Science played a leading role. Moderator Klaus Tochtermann (ZBW, Germany) discussed the issue together with

- Jessica Polka (ASAPbio, USA),

- Ana Persic (UNESCO, France),

- Paola Masuzzo (IGDORE, Belgium) and

- Tobias Opialla (Max-Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine, Germany).

Our Panel discussion is all about “Open Science in a Time of Global Crises”: Please welcome Ana Persic, Jessica Polka (@jessicapolka), Paola Masuzzo (@pcmasuzzo), Tobias Opialla (@opialla) and Klaus Tochtermann (@ktochtermann). #OSC2021

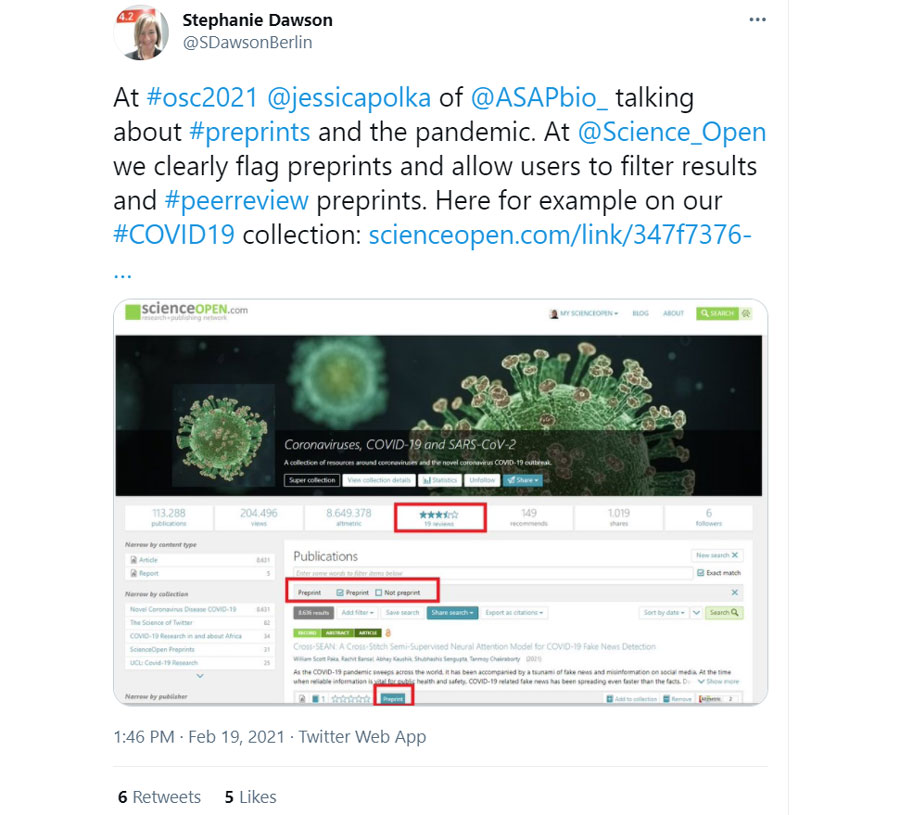

The panellists have already given an excellent overview with their opening statements regarding the points at which they and/or their institutions have advocated open practices in the management of the corona pandemic. For example, Paola Masuzzo and other volunteers have successfully campaigned for the Italian government to disclose data on the pandemic. The public must be informed, states Masuzzo. Jessica Polka reported that the platform ASAPbio has strongly campaigned for the preprint culture. At this point, however, the problems that occur if the public is confronted with non-peer-reviewed information from preprints soon came up for discussion.

Ever since the #WirVsVirus-Hackathon (German) of the German federal government, Tobias Opialla has been working on the digital platform LabHive with several volunteers. Their point of focus is the procurement of required resources and experts for diagnostic centres, to improve the testing capacities for SARS-CoV-2 via a culture of sharing. This also closes the gap between research and diagnostic laboratories, states Opialla. Ana Persic reported that UNESCO and its department “Division of Science Policy and Capacity-Building” (SC/PCB), in which she works, has campaigned for openness during the pandemic. There was, for example, a corresponding joint appeal from UNESCO, the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Commissioner for Human Rights at the United Nations (UN). And the “UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science” came at an opportune moment.

Various topics were then addressed, characterised by lively participation from the audience, and picking up on aspects that had already been addressed in several of the presentations. A general consensus held that the corona pandemic had clearly shown the advantages of open practices and that the wider public will also be involved, and must or would like to be informed. In a crisis openness should be the norm, not the exception. And the public ultimately has no sympathy for the opposite. Collaboration is a deciding factor in bringing different stakeholders and communities together but also in picking up on disciplinary and regional differences. The example of the preprints shows where action is still needed, above all in the field of scholarly communication.

Basically, preprints have been shown to be helpful, in order to disseminate findings rapidly and allow (public) discourse. But the partly unconsidered and/or unknowing seizing upon of preprints by the media and the interested public has shown that there is an increased need to explain how scientific discourse takes place and that, in the case of preprints, scientific peer review has not yet taken place. This primarily occurs in a closed context and many researchers are not yet used to commenting publicly.

So, good times for Open Science. Nevertheless the cultural transformation in the scientific system towards an Open Science ecosystem should not be taken for granted. Ultimately, the (voluntary) engagement of individuals continues to be important and, to this end, researchers need to invest time, which is not currently appropriately remunerated in the scientific system. The scientific incentive system simply needs to move faster, in order to establish the corresponding practices more widely. Panel moderator Klaus Tochtermann closed the discussion with the question of what the panellists had learned during the pandemic in relation to Open Science.

- Paola Masuzzo: Open Science is the only way. The only question is, how do we make Open Science a reality.

- Ana Persic: Die Corona-Krise hat einige der Herausforderungen ans Licht gebracht, die sich ergeben, wenn Dinge offen sind. Wir müssen die Zusammenarbeit zwischen allen Akteur:innen in der ganzen Welt herstellen.

- Tobias Opialla: Offenheit erfordert eine Menge Vertrauen. Die Pandemie hat Open Science ins Rampenlicht gerückt. Jetzt ist es wichtig zu definieren, was gute Open Science ist.

- Jessica Polka: Open Science ist während der Corona-Krise essentiell wichtig geworden. Es muss ein Prozess offener Kommunikation, Rückmeldungen und so weiter geben.

Conclusion: Open Science 2021 – where is the journey going?

Open Science has gained momentum worldwide and the corona pandemic has increased the tempo further, giving the development a noticeable shove forwards. It’s important to continue to use this potential. The disclosure of research data during the course of the pandemic shows how important collaborative work and information exchange is in coping with (global) crises. But deficits also clearly became visible. Particularly in the field of scholarly communication, it is clear that the public has too little insight into the world of science and its working methods. It has also been shown that the scientific community needs to be more active in communicating and explaining research results, to increase trust in science and its stakeholders.

In his closing statement, Klaus Tochtermann stressed that there will also be an Open Science Conference in 2022. Once again in Berlin, but as a hybrid event. We will take a close look at the lessons that can be learned from the purely digital Open Science Conference 2021 and also at what the needs of the community are. Ultimately we will try to combine the best of both worlds (face-to-face and online).

Links to the Open Science Conference 2021

- Programme of the Open Science Conference 2021

- Conference slides and posters from the Open Science Conference 2021

- Speakers at the Open Science Conference 2021

- Detailed report of the panel discussion on GenR

- Hashtag: #OSC2021

More tips for events

- Open Science & Libraries 2021: 21 Tips for Conferences, Barcamps & Co.

- ZBW-MediaTalk event calendar for further exciting events in the coming months

- Look back at the conference with the Password newsletter: Open Science is here to stay (German)

- Barcamp Open Science 2021: A GenR report

- Barcamp Open Science 2020: Learning to Make a Difference

- Open Science Conference 2019: The Recommendations are Being Implemented Now

- Open Science Conference 2018: Going into practice!

You may also find this interesting

- Open Science and Organisational Culture: Openness as a Core Value at the ZBW

- Open Science Podcasts: 7 + 3 Tips for Your Ears

- Digital Open Science Tools: How to Achieve more Openness Through an Inclusive Design

- Scoping the Open Science Infrastructure Landscape in Europe

- OpenCOVID19 Initiative

- Open Science in Times of Corona

This text has been translated from German.

Dr Guido Scherp is Head of the “Open-Science-Transfer” department at the ZBW – Leibniz Information Centre for Economics and Coordinator of the Leibniz Research Alliance Open Science. He can also be found on LinkedIn and Twitter.

Portrait: ZBW©, photographer: Sven Wied

Claudia Sittner studied journalism and languages in Hamburg and London. She was a long time lecturer at the ZBW publication Wirtschaftsdienst – a journal for economic policy, and is now the managing editor of the blog ZBW MediaTalk. She is also a freelance travel blogger (German), speaker and author. She can also be found on LinkedIn, Twitter and Xing.

Portrait: Claudia Sittner©

One Year of Open Access: The Journals Wirtschaftsdienst and Intereconomics Take Stock

The publishers of many journals that still appear behind paywalls are considering...