The 2019/20 Barometer for the Academic World: New Insights for Open Science?

What is the state of science in Germany these days? The Barometer for the Acadamic World has been dedicated to answering this since 2010, examining areas such as Open Data, Open Access, Peer Review and the question of how trustworthy scientific knowledge actually still is. We took a look at how much Open Science is in the current report.

by Claudia Sittner

The Barometer for the Academic World – not to be confused with the Science Barometer – can be seen as an inventory of the state of science in Germany. Following the previous surveys in 2010 and 2016, the 2019/20 survey results were published at the end of November 2020. They provide an overview of the working and research conditions at German universities and similar higher education institutions. The Barometer is published by the German Centre for Higher Education Research and Science Studies (DZHW).

8800 scientists from different disciplines and status groups were interviewed for the representative DZHW Scientist Survey. Their experiences and assessments paint a complex picture of Germany’s current science landscape: from working and research conditions to third-party funding, publication strategies or Open Data practices. We viewed the results of the survey with regard to their significance for Open Science in Germany’s university landscape and point out some interesting highlights.

The reliability of knowledge: Are trust levels decreasing?

In times of fake news and the replication crisis (German), it is unsurprising that the reliability of scientific knowledge is also doubted. While a still-robust average of 70 per cent of those surveyed expressed confidence in the knowledge produced in their respective fields, a fifth nevertheless estimate that less than 50 per cent of this knowledge is truly resilient. Room for doubt is particularly prevalent in psychology, life sciences and partly in economics. According to the Barometer for the Academic World, the first signs of a crisis of confidence are emerging here.

It is interesting to note that the assessments of the resilience of knowledge also vary widely within a given subject area. The study sees possible reasons for this in the fact that some researchers are not affected by this problem in their fields of work. Others simply seem to have no awareness of the problem. For example, in some subject areas, such as the social and economic sciences, the study achieved a bimodal distribution as a result of the survey. To put it simply, the response density curve has not one peak, but two. In this case, this suggests that there are large groups of people who, in a bundle, also represent opposing opinions and experiences regarding the trustworthiness of knowledge in their subject area.

The increased use of Open Science practices and the disclosure of all data in the research process could certainly help. As trust is an important resource for solidarity and unity in the research community, it is all the more important to counteract an impending crisis.

Knowledge transfer and social media: Open Access marginally relevant

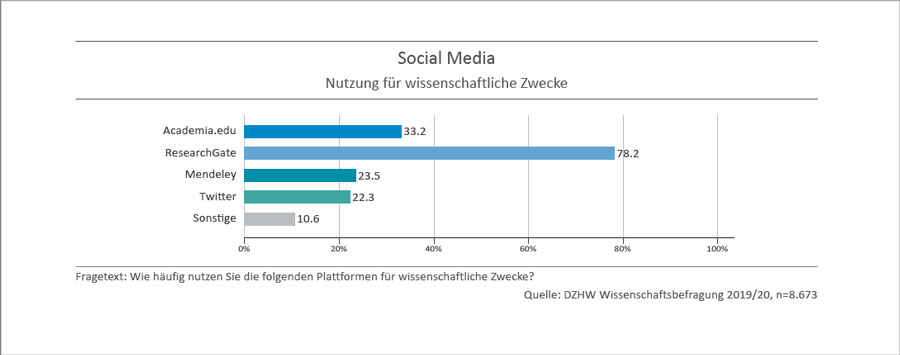

Knowledge transfer from German universities to other fields of knowledge is in full effect – and it varies greatly from subject to subject. A look at the researchers’ social media use reveals traces of Open Science. The study identifies four types of platforms for specific purposes:

- social networks that pointedly cater to scientists (for example Academia),

- literature research platforms,

- publication repositories and

- platforms for scholarly communication.

The platforms are used for very different reasons, be it literature research, networking, scholarly communication or making one’s own profile or work visible outside of the science system.

While some platforms are only used by certain subject groups, others (for example Github) seem to find interdisciplinary acceptance. The Open Access repository arXiv, in which preprints are published and presented to the specialist community (mathematicians/physicists), is highlighted in the Barometer because it is particularly well established in this subject area. There are comparable publishing portals in other subject areas, but these are not used as heavily and commonly as arXiv.

Open Data: Wish and reality

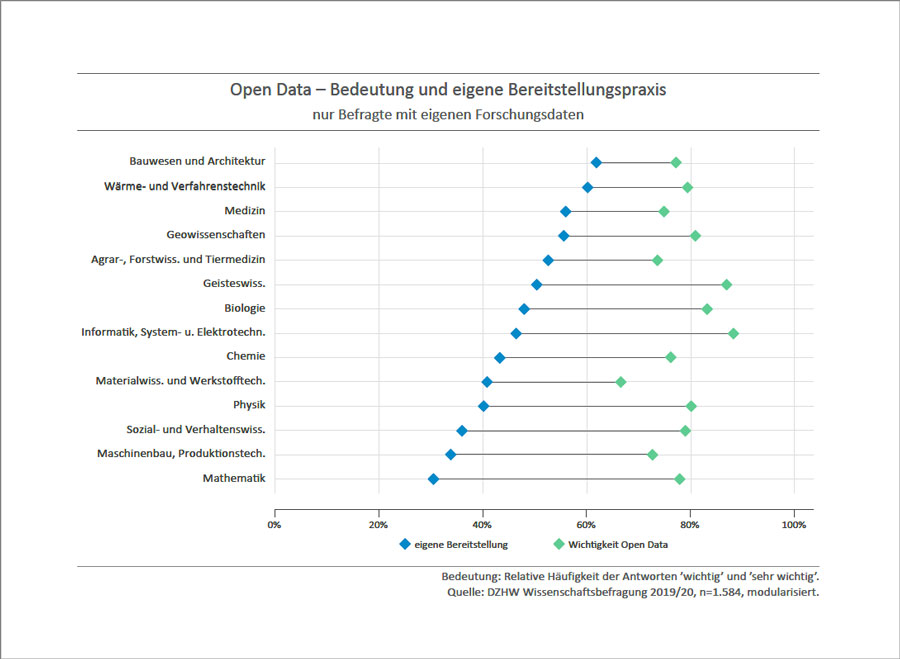

It is encouraging that a separate block of questions was dedicated to the topic of Open Data. It revealed that 87 per cent of the scientists work with research data and 78 per cent even collect some themselves. Only scientists with own research data were then interviewed about how they handle Open Data.

The results are not surprising: around 80 per cent of those surveyed consider the public provision of data to be (very) important, but only 45 per cent actually make their data publicly available. The “lacking recognition for provisioning activities” counts as one of the reasons for this low number.

It is a reason that can be found in many Open Science activities, and that is deeply rooted in the scientific incentive system. However, this also provides a good starting point for science policy-makers to promote Open Data activities by creating incentives.

Peer review system: Is a crisis on the horizon?

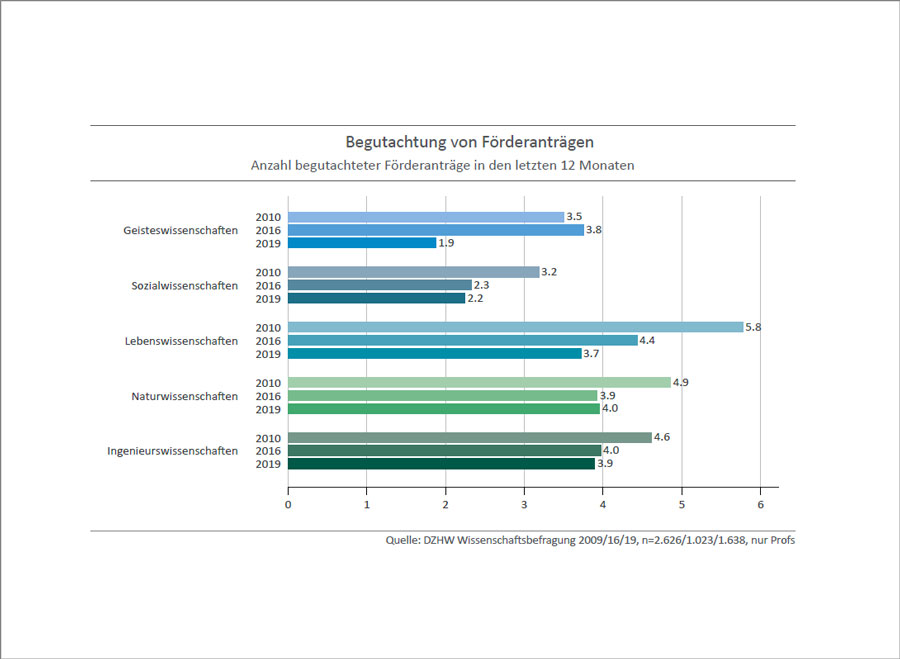

The Barometer for the Academic World also examines whether the German peer review system is facing a crisis. After all, the last 20 years have seen the number of worldwide publications double from 1 million to 2 million. To figure that out the Barometer uses two indicators as a kind of stress test for the peer review system: assessment effort per person and the quality of the assessment.

However, both indicators give no cause for concern. Even though the number of assessments and funding applications seems to be high (ten journal articles and three funding applications per person and year), the assessment effort has evidently decreased – probably also because the assessing is now carried out by more individuals.

The second indicator also points out that the peer review system is stable. That is because from the scientists’ perspective, the quality of the assessments altogether did not change in recent years (34.4 per cent). These estimations concern not only the assessment of manuscripts, but also of funding applications.

This status is not only a hopeful sign for Open Science: it means that scientists are able to keep the peer review system stable.

Research funding: Matthew effect and dissatisfaction

Based on the applications submitted to the German Research Foundation (DFG), the study examines the selection processes’ acceptance in research funding. Based on some of the interviewees’ answers, it can be deduced that many of them see a Matthew effect in the research system. The Matthew effect is commonly referred to as successes based on past – rather than current – performance. The reputation of the individual and the university therefore plays a decisive role here.

This is also the reason for the frustration that “the same old players” receive research funds, and that renowned researchers from established universities are preferred in the allocation of funds. A lack of neutral experts is also lamented in this respect. The direct competition often takes over the assessment, meaning that a fear of idea theft is constantly present. However, this apprehension has decreased by 10 percentage points as compared to the 2010 survey. Deploying international experts is seen as a possible solution.

In the area of research funding, therefore, some obstacles can unfortunately be identified which also apply to the development of the Open Science ecosystem. That is because the “top dogs” have little reason to commit themselves to fair research funding that does not take reputations and career status into account. However, the fact that the fear of idea theft, which makes scientists hesitate to share ideas and data, has decreased is positive.

Publishing system: Open Access barely plays a role

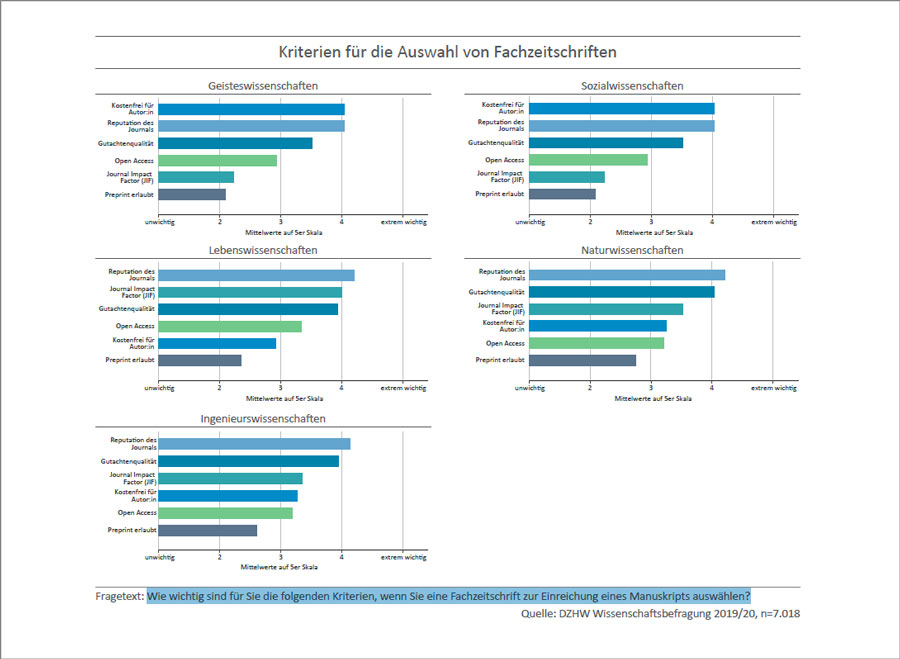

Looking at the publishing system, those who read the Barometer for the Academic World quickly realise that for scientists, Open Access does not play a major role in selecting a journal to publish their contributions. First of all, Open Access only appears in one spot in the publication block of the survey: in the question “How important are the following criteria for you when selecting a journal to submit a manuscript?”. “Open Access” is one of six options given.

Across all subject groups, the scientists’ responses suggest that Open Access is not a relevant selection criterion for them. With the five-step selection scale, the answers are usually on the mean value (reasonably important). Even less important to them is only whether the journal allows preprint publication of the article – which also confirms, however, that Open Access does not play a role at least in the selection of suitable journals, and is at most a (positive) side effect. The important factors are not surprising: reputation, costs for the authors and the quality of the peer reviews.

However, few people think much of the idea of publishing anonymously to compensate for the Matthew effect (reputation of the individual/university). Only 30 per cent would be willing to anonymously publish their results in a journal. The respective career level and age effects are also relevant here: the higher up the career ladder, the less conceivable it is for respondents to publish anonymously.

From an Open Science perspective, however, this idea could be quite interesting, as it symbolises a kind of fairness that focuses purely on content and less on past successes.

Conclusion: Barometer for the Academic World highlights starting points to promote Open Science

In conclusion, it can be said that above all, the Barometer reveals long-known barriers and challenges that stand in the way of Open Science being able to continue spreading in the German science system. At the same time, they illustrate good starting points for science policy to promote Open Science and create worthwhile incentives for open practices.

This might also interest you

- Future Report: Who can transform scholarly publishing and communication?

- Open Economics: Study on Open Science Principles and Practice in Economics .

- Open science infiltrates the engine room of research: ZBW panel at the German Economic Association annual conference 2019.

- Guidelines: How to implement Open Peer Review and foster its adoption .

- Social Media and Scientific Communication: A minor role for Open Science in the statement?.

This text has been translated from German.

Claudia Sittner studied journalism and languages in Hamburg and London. She was a long time lecturer at the ZBW publication Wirtschaftsdienst – a journal for economic policy, and is now the managing editor of the blog ZBW MediaTalk. She is also a freelance travel blogger (German), speaker and author. She can also be found on LinkedIn, Twitter and Xing.

Portrait: Claudia Sittner©

View Comments

Online Events: Mastering Hurdles on the Path to a Digital Future – the Example of the YES! 2020

2020 has presented major challenges for many event organisers, including those...