ChatGPT & Co.: When the Search Slot turns into an AI Chatbox

Generative language models and AI-supported searches are currently enjoying a rapid triumph. More and more search engines are relying on robotic chats to replace searching with finding. But what are the implications of this – and what does it mean for academic libraries?

by André Vatter

The claim that AI language models are here to stay should be irrefutable by now. Although just introduced to the public in November 2022, ChatGPT has made rapid progress in this short time. How rapid? Let’s compare: After its founding, it took Twitter two years and Facebook ten months to build up a base of one million users. ChatGPT managed to reach this milestone in only five days. Two months after its launch, almost forty percent (German) of all Germans said they had heard of the chat robot or had already tried it.

A brutal race

But as impressive as the private adoption rate is today, what is more exciting is the escalations that ChatGPT has caused hitting the corporate world. Microsoft’s announcement of its plan to integrate the generative language model into its own search engine Bing caused sheer panic among the undisputed global industry leader Google. Google has been tinkering with an AI-supported web search for some time, but it has not yet been able to demonstrate that it is really ready for the market. There is a name, “Bard“, but CEO Sundar Pinchai is silent about concrete integrations. On the other hand, Microsoft was able to announce just a few days ago that its own search engine, which had hardly been noticed by users for decades, had to cope with a sudden rush of visitors:

“We have crossed 100M Daily Active Users of Bing. This is a surprisingly notable figure, and yet we are fully aware we remain a small, low, single digit share player. That said, it feels good to be at the dance!”

Redmond, Washington, is in an AI frenzy. In the future, there will hardly be a business area at Microsoft – whether B2B or B2C – in which ChatGPT does not play a role.

The disruption is also leaving its mark on the smaller competitors. Brave Search, the web search engine created by the US browser manufacturer Brave Software Inc. recently got a new AI feature. The “Summarizer” not only summarises facts directly at the top of the search results page, but also provides relevant content information for each result found. There are also changes at the privacy-focussed search engine DuckDuckGo, which has just launched “DuckAssist“. Depending on the question, the new AI feature taps Wikipedia for relevant information and offers concrete answers while still being on the search results page. But this is just the beginning: “This is the first in a series of generative AI-assisted features we hope to roll out in the coming months.”

All these integrations of AI language models into search engines are not about creating extensions to the existing, respective business model. It’s about a complete upheaval in the way we search the web today, how we interpret results and understand them.

How finding replaces searching

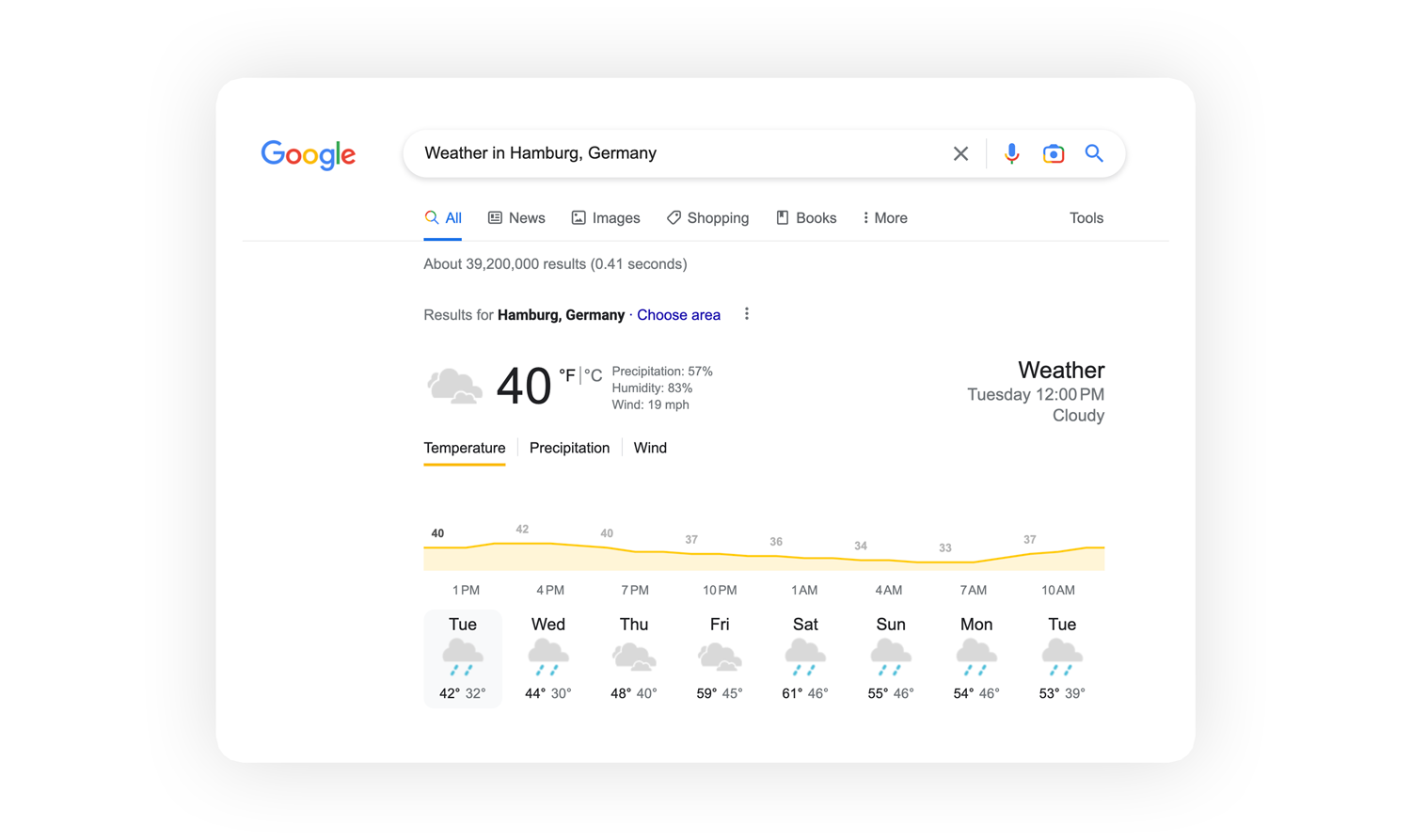

Whereas the previous promise of search consisted of an effortful “I’ll show you where you might find the answer”, in combination with AI it suddenly advances to: “Here’s the answer.” Since their invention, search engines have only ever shown us possible ways where answers to our questions might be found. In fact, it has never been the inevitable goal of advertising-based business concepts to provide users with a quick answer. After all, the goal is to keep them in one’s ecosystem as long as possible in order to maximise the likelihood of ad clicks. This is also the reason why Google at some point began to present generally available information – such as times, weather, stock market prices, sports results or flight information – directly on the search results pages (SERPs), for example, in the so-called OneBox. The ultimate ambition is that no one leaves the Googleverse!

Intelligent chatbots, like ChatGPT, get around this problem. On the one hand, they transform the type of search by replacing keywords with questions. Soon, many users are likely to say goodbye to so-called “search terms” or even Boolean operators. Instead, they’ll learn to tweak their prompts more and more to make their communication with the machine more precise. And on the other hand, intelligent chatbots reduce the importance of the original sources; often there is no longer any reason to leave the conversation. Those who search with the help of AI want and get an answer. They do not want a card catalogue with shelf numbers.

Despite all answers, questions remain open

We can already see that comfort does not come without critical implications. For example, with regard to the transparency of sources that we may no longer be able to see. Where do they come from? How were they selected? Are they trustworthy? Can I access them specifically? Especially in the scientific sector, reliable answers to these questions are indispensable. Other problems revolve around copyright. After all, AI does not create new information, but relies on the work of journalists who publish on the internet. How will they be remunerated if no one reads their texts and only rely on machine summaries?

Data protection concerns will not be long in coming. In communicating with the machine, a close relationship develops over time; the more it knows about us and can understand our perspective, the more accurately it can respond. In addition, the models need to be trained. Personalisation, however, inevitably means a critical wealth of data in the hands of third parties in return. In the hands of companies that will have to build entirely new business models around a question-answering game – quite a few of which, if not all, will be ad-supported.

AI provides answers. But not really to all questions at the moment. Search will change radically in a short time. Academic libraries with online services will also have to orient themselves accordingly and adapt. Perhaps the “catalogue” as a static directory or list will take a step back. Let’s imagine for a moment the scenario of an AI that has access to a gigantic corpus of Open Access texts. Researchers access several sources simultaneously, have them sorted, summarised in terms of content and classified: Have these papers been supported or falsified? The picture that emerges is of a new mechanism for making scientific knowledge accessible and comprehensible. Provided, of course, that the underlying content is openly accessible. From this perspective, too, here is once again a clear plea for Open Science.

So, how do academic libraries implement these technologies in the future? How do they create source transparency, how do they build trust and which disciplines of media literacy move to the foreground when new, machine-friendly communication is part of the research toolbox? Many questions, many uncertainties – but at the same time a great potential for the future supply of scientific information. A potential that libraries should use to actively shape the unstoppable change.

This text has been translated from German.

This might also interest you:

- Hackathon Coding.Waterkant: How to Improve Library Services Through Chatbots and Artificial Intelligence

- Horizon Report 2022: Trends Such as Hybrid Learning, Micro-certificates and Artificial Intelligence are Gaining Traction

- AI in Academic Libraries, Part 1: Areas of Activity, Big Players and the Automation of Indexing

- AI in Academic Libraries, Part 2: Interesting Projects, the Future of Chatbots and Discrimination Through AI

- AI in Academic Libraries, Part 3: Prerequisites and Conditions for Successful Use

View Comments

Digital Trends 2023: Bridging the Gaps Between Home Office Autonomy and Collaboration, Mental Wellbeing and Skills Shortage

The pandemic has long-lasting effects on the way we work. Asynchronous work is here...