Barcamp Open Science 2023: So Much has Happened and so Much Still Needs to Happen!

The Barcamp Open Science already went into its ninth round in 2023, hybrid for the first time. The good news: a hybrid format works for a barcamp as well. Together with some session moderators we summarise what happened at this year’s barcamp.

by Evgeny Bobrov, Christian Busse, Julien Colomb, Tamara Diederichs, Tamara Heck, Renu Kumar, Peter Murray-Rust, Daniel Nüst, Merle-Marie Pittelkow, Lozana Rossenova, Guido Scherp

When we (the Barcamp Orga Team) were planning the ninth Barcamp Open Science, we were faced with the question: back to a face-to-face event or online, and if we choose a face-to-face event, could a hybrid format work at a barcamp? Hybrid works! Especially thanks to the technical progress and the appropriate premises at Wikimedia. A barcamp is a format that can have its best effect when meeting in person. But for us, hybrid also means openness towards those who, for various reasons, cannot come to Berlin. This year, we had 40 participants on site and 60 more taking part online, including people from India. Online participants could follow the barcamp in the main room (opening, ignition talk, session planning), but also participate in sessions in hybrid rooms. In one case, a session was even moderated remotely.

This year, we were particularly pleased that half of the participants took part in the Barcamp Open Science for the first time, and that many of them proposed and moderated a session straight away. The barcamp thus also contributes to enlarging the ‘Open Science bubble’ bit by bit.

There has never been a lack of topics at the Barcamp, though some of the topics are recurring, of course. Every year new aspects are included in the discussion. This year for example, Open Science for climate justice and bringing Open Science into ‘schools’, that is what role can (educational) organisations play in the context of knowledge justice. The traditional ‘Ignition Talk’ also brings new and relevant topics to the table. It was held this year by Peter Murray-Rust on the topic ‘Why do I do Open Science?’. He emphasised how important open knowledge is for society as a whole, especially in tackling the climate crisis. He is therefore actively involved in the #semanticClimate project, in which tools are being developed to make knowledge from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports by the UN semantically available.

Some of the session moderators have summarised their sessions and their results below.

Indicators for Researcher Contributions to Wikidata

by Evgeny Bobrov

Wikidata and more generally knowledge graphs (KGs) hold a lot of promise to make knowledge, prominently including scientific knowledge, available in a structured way for automated applications. With the advent of Large Language Models (LLMs), there is much discussion about the future role of KGs, but in terms of quality-assurance, traceability, and speed KGs are far superior to LLMs. Thus, as Denny Vrandecic describes in his talk ‘The Future of Knowledge Graphs in a World of LLMs’, they will only continue to grow in importance. Positions of ‘Wikimedian in Residence’ are becoming increasingly common, as at the University of Edinburgh or the University of Virginia. Given these developments, we anticipate that entering knowledge generated at research institutions into KGs will become increasingly important for institutions and a standard practice for researchers.

However, if this is to become a common practice, it needs to be rewarded, and the question arises of how to monitor and reward sharing of knowledge in Wikidata and other KGs. This was the main topic of the session, although we ventured into other Wikidata-related topics as well. In particular, one participant was disillusioned with Wikidata, as many necessary relations were as yet undefined, and it was generally still too limited. Thus, entering data into Wikidata came at the cost of simplifying or sometimes even distorting knowledge. The opinion was also voiced, however, that this is legitimate as a start and should not prevent researchers from extending Wikidata. It was also mentioned that the NFDI is considering using Wikidata as an infrastructure, and that the Volkswagen Foundation in its funding for data management tasks might include entering knowledge into Wikidata. A sideline of the discussion, which would warrant more attention, is in how far Wikidata should contain all knowledge, or how else could it be organised, for instance in a federated way.

Specifically regarding monitoring and incentives, the following aspects were discussed:

Own contributions

- Number of contributions to Wikidata

- Number of links, own contributions receive in other entries

- Number of references to entries in scientific works

- Fraction of entries which have been validated by others

Community work:

- Number of entries reviewed or validated

There is already work in this direction, for example, to allow a tracking of citations to Wikipedia contributions, and this metric is mentioned in the Metrics Toolkit. However, for Wikidata, there would need to be a method in place to reference sources in a much more granular way than is currently common

Indicators as listed above, which can be conceived of as a type of nanopublication, could then be aggregated and for instance be used in CVs. There was agreement, however, that these metrics are not fundamentally different from article and citation metrics, and can thus lead to an overemphasis of quantity as well as be gamed. However, we could not come up with more unique metrics in this session, which would be less quantitative and/or less easily gamed.

Legislative Measures to Increase Data Availability

by Christian Busse

The central question for this session was whether legislative measures that aim to increase the availability of data held by private or public entities are considered as useful and appropriate from the Open Science perspective. The backdrop to this is a number of ongoing legislative initiatives on the European DataAct – at this point finalised, but not passed yet, European Health Data Space (EHDS) Regulation – still under discussion by the EU Council) and the German federal level (proposed ‘Forschungsdatengesetz’ (German) / Research Data Act – still at a draft stage) for which provisions have been discussed that would/will enforce private and public entities to share their data with researchers.

After a quick overview about the provisions at hand, the participants started with a discussion that covered a broad range of aspects, but had three main key take-aways. First, coercing private entities into data sharing was NOT perceived as a constructive measure by the participants, as providing data (that is complying to the legal requirement) does not guarantee good data quality. Second, the participants saw greater promise in trying to utilise data from public entities, as financial compensation would be less of an issue. However, the participants also agreed that this would require a more service-oriented mindset in the public administration and that empowering and up-skilling public employees (for instance to become data stewards, product owners, and so on) would be helpful. Third, a marketplace solution in which (public and private) entities can offer their data products for research was also considered an interesting option by the participants, although the ultimate outcome would depend on numerous parameters of the marketplace and hence is hard to predict.

New Forms of Communication

by Christian Busse

The social medium X (formerly known as Twitter) has been in turmoil for a while. In this session, the participants discussed whether and how this affects their communication strategies when promoting and discussing Open Science online. There was a consensus among the participants that the goal should be to serve a broad audience and that this will require more channels, now that some people and communities are moving away from X. Mastodon is considered an interesting alternative due to its federated character, but the verdict is still out whether it can serve as a long-term replacement. Moving beyond the individual platforms, the participants then discussed ways to organise (scientific) quality control in media that do not primarily serve science. How can we validate that an account belongs to a given person, that a person is really a member of a given institution and that a person is really an expert in a given field of research? While there are some technical solutions to some aspects of this (for instance Mastodon’s link verification), this requires trusted entry points that are controlled by the community.

An Exit Strategy for Github

by Julien Colomb

In this session, we tried to collect strategies to make Open Science projects independent of GitHub. While GitHub is a very nice platform, it may become less nice at any time (and there may already be some issues with Microsoft tracking all your activities on the platform). We saw with the formerly Twitter that platforms can become unusable, such that relying on one platform for one specific scholarly work can be dangerous.

In order to get less dependent on GitHub and be able to move a community to another platform if needed (or wished for), we collected different strategies:

- Push the content into GitLab or other alternatives: this makes the code and document easy to access without GitHub, but a lot of community work and ongoing activities would still be lost (issues, PR, forks, discussions,…). This technical solution does not deal with moving the community on a different platform.

- Get your community on different platforms. For example, use a forum, a chat-application (discourse) on top of GitHub. So if you need to move from one platform to another, the community still has other communication channels that are still working.

We then talked about development in decentralised systems: Forgejo is planning to make different instances interoperable. Indeed, having different GitLab instances in different universities in Germany makes it difficult to have collaborators in other universities (a new account is needed for each instance). Alternatively, we may see the development of European, institutionalised GitLab instances like EUDAT GitLab Repository?

Bringing Open Science Into 'Education'

by Tamara Diederichs

A group of five people from different backgrounds participated in this session. The basic question was about Open Science and the connection with education. The session, which was also recorded and whose result is available as a transcript in the pad, said that we need a cultural change and that a cultural change to Open Science can happen through education and the organisations there.

The following questions were discussed:

- What can organisations do to bring Open Science to the world or society?

- What kind of structures for organisations or what kind of structures can be built with organisations to bring Open Science into the society?

- Are there Open Science strategies and organisations and which ones?

- Are there already movements that are taking Open Science in Education?

Some Conclusions:

- There are different organisations that can promote Open Science, for instance universities or schools.

- It is important to be transparent yourself and to inform others why transparency is important.

- Collaboration should be an important approach in knowledge generation.

- It is difficult to get people outside the Open Science bubble excited about Open Science.

- Organisations need Open Science strategies.

- The traditional education and science system can be described as a barrier to Open Science.

Open Scholarship Indicators

by Tamara Heck

Quite a few institutions have passed Open Science policies or guidelines, in which they admit to the principles of Open Science and recommend good practices for their research employees. According to policy templates, each policy may include aspects of ‘monitoring policy compliance’, that are actions on how we can assess the impact of the policy on daily research practices. However, the challenge is to measure Open Science practices properly, which means to make the evaluation fair and transparent, and not availing any non-desirable practices.

Currently, the implementation of an open research culture is not fully measured. The most popular example of assessing the development of Open Science is counting Open Access publications (in relation to closed publications). Current dashboards aim at showing more quantitative data of research output by institutions, like Helmholtz and the Charité.

Looking at the quantified Open Science-related output, it is important to say that not all research practices are easily quantifiable. Moreover, such indicators should be defined according to domain specific aspects and their specific use case. Comparing numbers between different domains or entities can be misleading. Another challenge with semi-automated data collection for such indicators is missing or false metadata in our digital infrastructures. If such difficulties are reduced adequately, these indicators can be measured over longer time periods to see how parameters evolve and to better put the relative numbers into perspective.

Conclusion: Indicators can be used to measure how we evolve in Open Science practices over time. However, the development of such measures needs careful consideration, both on technical aspects like metadata and data collection, and on social aspects like the understanding and appreciation of researchers.

Open Science for Climate Justice

by Peter Murray-Rust and Renu Kumari

This 45 minutes long session was about the role of semantic climate tools used to simplify the chapters from IPCC reports and make these chapters understandable by any person in the world irrespective of their age and education level. The demo was about the tools pyamihtml, pygetpapers and docanalysis. The colab notebook shared in the demo session contains the information to use all the tools and was applied to view one of the output like a word cloud for different useful keywords from the searched literature based on the search query ‘climate justice and Africa’. It nicely explains the terms which are very significant and prevalent for the climate study.

Open Science - Sticks and Carrots for Change

by Daniel Nüst

A transition to Open Science that is sustainable requires a cultural change in all aspects of academic research, even if this requires questioning long-held beliefs and established practices. I proposed that to achieve such a lasting shift in funding, sharing, evaluation, and career building practices that transcends nations and cultures, one needs to think about both incentives and encouragement – carrots – and policy and requirements – sticks!

In the session, the participants started by collecting the stakeholders of a cultural change, and identified rather classical roles in academia across different career stages, for example funders, professors, students, librarians, etc. An excellent resource that was shared in the context is the article ‘Promoting Open Science: A Holistic Approach to Changing Behaviour’ that includes suggestions for these different stakeholders within the academic system. It was noted that bottom-up initialisation of behavioural change works to some degree, but top-down was also needed. This perspective adds another dimension when thinking about cultural change. It was specifically discussed that leadership in organisations and communities needs to be involved, since waiting for a generational change (the Open Science enthusiasts of students today become professors of tomorrow) may take too long. The LIBER Citizen Science working group was pointed out as an initiative that successfully ran a course targeting leadership specifically in the context of Citizen Science, amongst other stakeholder-specific documentation (Citizen Science for Research Libraries – A Guide) – another good idea! With the question of generational change in mind, the discussion then shifted towards the question whether ‘better education’ can implement a cultural change. The experiences here were controversial. One participant reported, that in one field of research, thinking about openness ends with Open Access, whereas another pointed out that the Open Science communities and initiatives quickly tend to focus on education, but these activities don’t seem to have lasting impact: people participate in workshops, but don’t change their practices, and early career researchers don’t have the power to introduce change on the needed large scale. The psychologists in the group pointed out the helpful idea that later career stages struggle to embrace change due to a very human trait and bias: professors think their approach was successful, so it is the right one. Possibly reflecting the career stages of the group members, but also representing experiences as Open Science proponents, the majority was in favour of top-down changes, for instance clear incentives and different evaluation criteria. For such a policy-based approach, major activities such as COARA and DORA were introduced into the conversation and new to some of the participants. The latter was presented as a clever approach to shift institutional policies in a sustainable way. Because the in part abstract goals the declaration pursues can then enable individual members of the signing organisations, who want to advance researcher assessment for example in hiring, to justify changes.

The psychologists also were a bit more exposed in the meeting, as the group shifted their conversation to Psychology as a discipline, which some saw as leading in Open Science practices due to the impactful replication crisis. When realising the questionable replicability of important foundational scientific works, the discipline did shift practices. Maybe ‘having a real crisis’ as a discipline and being lucky that people want to learn from it is the only way for change? Hopefully not.

Finally, the idea that one can draw from the experiences of Citizen Science was put forward but argued against, too. On the one hand, similar to approaches to decolonization, one should think about bringing knowledge back to the public and not just within the world of research. On the other hand, the academic work in Citizen Science was not seen as more advanced in Open Science practices than other disciplines, falling into the same traps of publish or perish, slow change, and further more.

All in all, the session did in some moments reflect a group therapy session. Almost every participant was actively working towards a cultural change, but as individuals or small initiatives, many also often feel quite powerless. The ‘venting’ and sharing that happened during the session was just as important as the useful resources that were shared. The fun and open exchange helped to find new energy to push towards a cultural change in academia, which was seen as needed by all joining and contributing to the discussion.

To wrap up the session, everybody was invited to come up with “the one thing” that one would change to achieve a sustainable shift in academic culture. The following items were mentioned, and shall be listed here in full to value all inputs and give you more food for thought:

- Incentive structure that gives people the possibility to do good (5 times), like more permanent positions, incentives that understand progress is slow, incentives that work towards a vision for openness, no publication-based dissertations

- community building / ‘peer pressure’

- force whole communities to move together

- establish understanding that ‘open is better’

- top-down pressure from (public) funders

- document good practices really well, leading to amplification

- find an agreement on ‘the right way’ to do research (with the help of technology), making academia a better community

- more team science

Creating A Shared Definition of Open Science

by Merle-Marie Pittelkow

During the ignition talk, Peter Murray-Rusk asked the audience to raise their hands if they had a clear idea of what Open Science was. In a room full of Open Science enthusiasts and advocates, I was expecting people to confidently throw their hands in the air, but only few raised their hands. This lack of a response inspired this session aiming to create a shared understanding of what Open Science means to the participants of the Barcamp Open Science. My hope was that this would foster and support the following discussions and avoid miscommunication between participants.

While you can find many definitions of Open Science online (e.g., as provided by FOSTER or UNESCO), there are individual differences in how these are interpreted and applied in practice. As a group we concluded that a monolithic, central definition of Open Science is not useful as what constitutes Open Science is context dependent and varies for example per scientific field, institutional context, and policies. Still, we were able to create a working definition of Open Science within the context of this event. The group agreed on the following aspects of Open Science:

- Sharing data

- Sharing results

- Sharing processes and methods (for instance ResearchEquals)

- Cocreation of a scientific process – outside of academic journals, more communal

- Digital long term storage (like NFDI structure, repositories) with sufficient documentation for the possibility to reuse the data in the long term

- Reflexive notes

- Preregistration; Registered Reports

- Pre-prints

- Replication

- Ensuring interoperability and then also doing the linking of data (part of FAIR data)

Semantic Annotations

by Lozana Rossenova

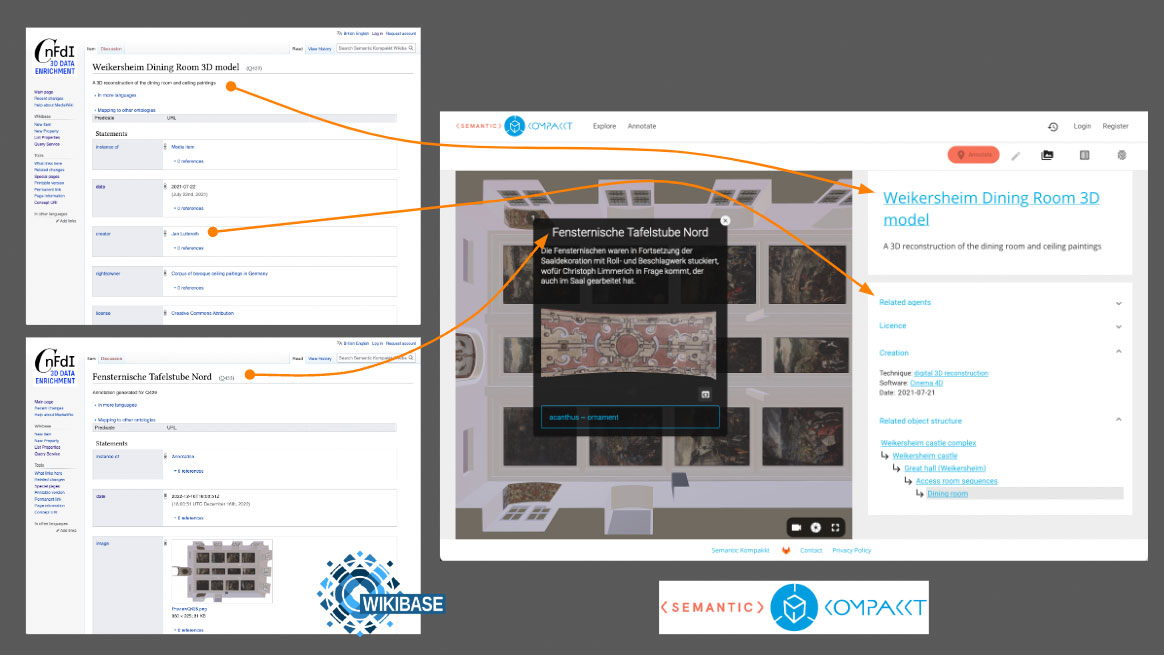

In this session, we introduced the ongoing work on semantic annotations for cultural heritage at the Open Science Lab, TIB, part of the NFDI4Culture consortium. The main tools we’re developing are focusing on the annotation of 3D models, and other multi-media cultural heritage representations. Annotations are structured in Linked Open Data (LOD), enriched with a standard authority file data and made accessible via a SPARQL endpoint. The integrated toolchain is called Semantic Kompakkt and consists of Wikibase (for metadata storage as LOD) and Kompakkt (for publishing and annotating 2D, 3D and AV media). OpenRefine is used as main data cleaning, reconciliation and upload tool. The session focused on the open, iterative approach towards the development of the toolchain around specific use-cases with partner institutions of NFDI4Culture. We also discussed the role of Wikidata in facilitating federated queries and the benefits of working with semantic data in general, including the introduction of structured vocabularies and authority file data in the data enrichment process. The final point of discussion touched upon the Antelope service (also from OSL / NFDI4Culture) for terminology search and integration into the annotation workflow. A core focus of the whole session was the use of Open Source software and how further development of Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) in research contexts can both draw upon and support the maintainer communities. The source code from the NFDI4Culture project is available on GitLab.

Data links in the Semantic Kompakkt toolchain. Credit: Lozana Rossenova, CC-BY.

We Will Continue

We would like to thank all participants for their session proposals, which contributed to exciting discussions and the remarkable atmosphere especially on site, but also online. We are happy about a very active and constructive community. Thus, we will continue the hybrid barcamp and are already looking forward to next year’s tenth anniversary. The Barcamp Open Science is our personal Open Science success story! In spite of all the successes the movement has achieved, so much still needs to happen.

Barcamp Open Science 2023

This year’s Barcamp was again accompanied by the Open Science Radio team, who interviewed numerous session moderators. These episodes are currently being published bit by bit and can be found here.

Evgeny Bobrov is Project Leader for Open Data & Research Data Management at the QUEST Center for Responsible Research, which is a part of the Berlin Institute of Health at Charité. He addresses these topics from diverse perspectives, including researcher consulting, teaching, policy, and monitoring. A major focus currently is defining and evaluating the openness of datasets in a thorough way.

Christian Busse is a team leader at German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ). He has a medical background and holds a PhD in experimental immunology. His current work focuses on comprehensive solutions for the management of immunological data. Christian is co-chair of the Standards working group of the AIRR Community and a member of the NFDI4Immuno consortium. He can be found on Mastodon and ORCID.

Julien Colomb is a former neuro-geneticist (10 years of research on fruit fly memory and behaviour), and has been exploiting his interest in Open Research, working on reproducible data analysis and research data management, as well as more recently on Open Source research hardware. He is presently working on ways (technical and social) to implement the principles of FAIR and Open Data in the lab workflow and ways to foster collaboration between researchers via the SmartFigure Gallery and the GIN-Tonic projects. On the other hand, he is fostering the development of open hardware in academia and beyond, inside the OpenMake project. He can be found on Mastodon.

Tamara Diederichs is Co-CEO at NDT.net and responsible for content and publishing. She has a scientific background with a focus on formal and non-formal adult learning, knowledge transfer, organisational learning and Open Science. She is also a researcher and honorary lecturer at the Department of Educational Sciences at the University of Koblenz. Among others, she can be found on the following channels: LinkedIn and ORCID.

Tamara Heck works at the Information Centre for Education at DIPF | Leibniz Institute for Research and Information in Education. She investigates how digital infrastructures can facilitate and influence information seeking, and how they can support Open Science practices. Tamara Heck can be found on X and LinkedIn.

Renu Kumari is working as Programme manager at #semanticclimate, NIPGR, New Delhi, India.

Peter Murray-Rust is a chemist currently working at the University of Cambridge. As well as his work in chemistry, Murray-Rust is also known for his support of Open Access and Open Data.

Daniel Nüst is a research software engineer and postdoc at the Chair of Geoinformatics, TU Dresden, Germany. He develops tools for open and reproducible geoscientific research and is a proponent for open scholarship and reproducibility in the projects NFDI4Earth, o2r, KOMET, and CODECHECK. He can be found on Mastodon, LinkedIn, GitHub, ORCID, and many more platforms via Nordholmen.

Merle-Marie Pittelkow is a postdoctoral researcher at the QUEST Center for Responsible Research, Berlin Institute of Health at Charité Berlin. In her work, she focuses on research ethics and increasing transparency in informed decision making. As a former OSCG board member and co-chair of ReproducibilitTEA at the University of Groningen, she has been an advocate of Open Science since her PhD.

Lozana Rossenova is a postdoctoral researcher at the Open Science Lab at TIB – Leibniz Information Centre for Science and Technology, and works on the NFDI4Culture project, in the task areas for data enrichment and knowledge graph development for cultural heritage research data. She serves as Wikibase community manager within NFDI4Culture and is a co-founder of the Wikibase Stakeholder Group. She can be found on Mastodon.

Guido Scherp is Head of the “Open Science Transfer” department at the ZBW – Leibniz Information Centre for Economics. He can be found on Mastodon and LinkedIn.

All photos: Bettina Ausserhofer©

View Comments

Open Science Award Winners: Insights and Findings From a Pioneering Practice

Interview with Ronny Röwert In his doctoral project, Ronny Röwert (TU Hamburg)...