Nudging Open Science: Useful Tips for Academic Libraries?

Nudging is an approach used in behavioural research to bring about certain positive changes in behaviour through "nudges". Can it also be usefully applied to change the scientific ecosystem?

by Claudia Sittner

An international group of eleven behavioural scientists from eight countries (Australia, New Zealand, Germany, Austria, Poland, USA, Netherlands) recently addressed this question in the report „Nudging Open Science“ and developed recommendations for action for seven groups in the scientific system. Academic libraries are one of these groups. The other groups (they are called “nodes” in the report) are researchers, students, departments and faculties, universities, journals and funding organisations. The team of behavioural scientists classifies each of these groups and gives practical tips on who can nudge each group, and how, to practice more Open Science. However, the report does not contain any approaches on how libraries themselves can actively nudge other stakeholders. We present approaches and results of the report with a special focus on academic libraries.

What is nudging?

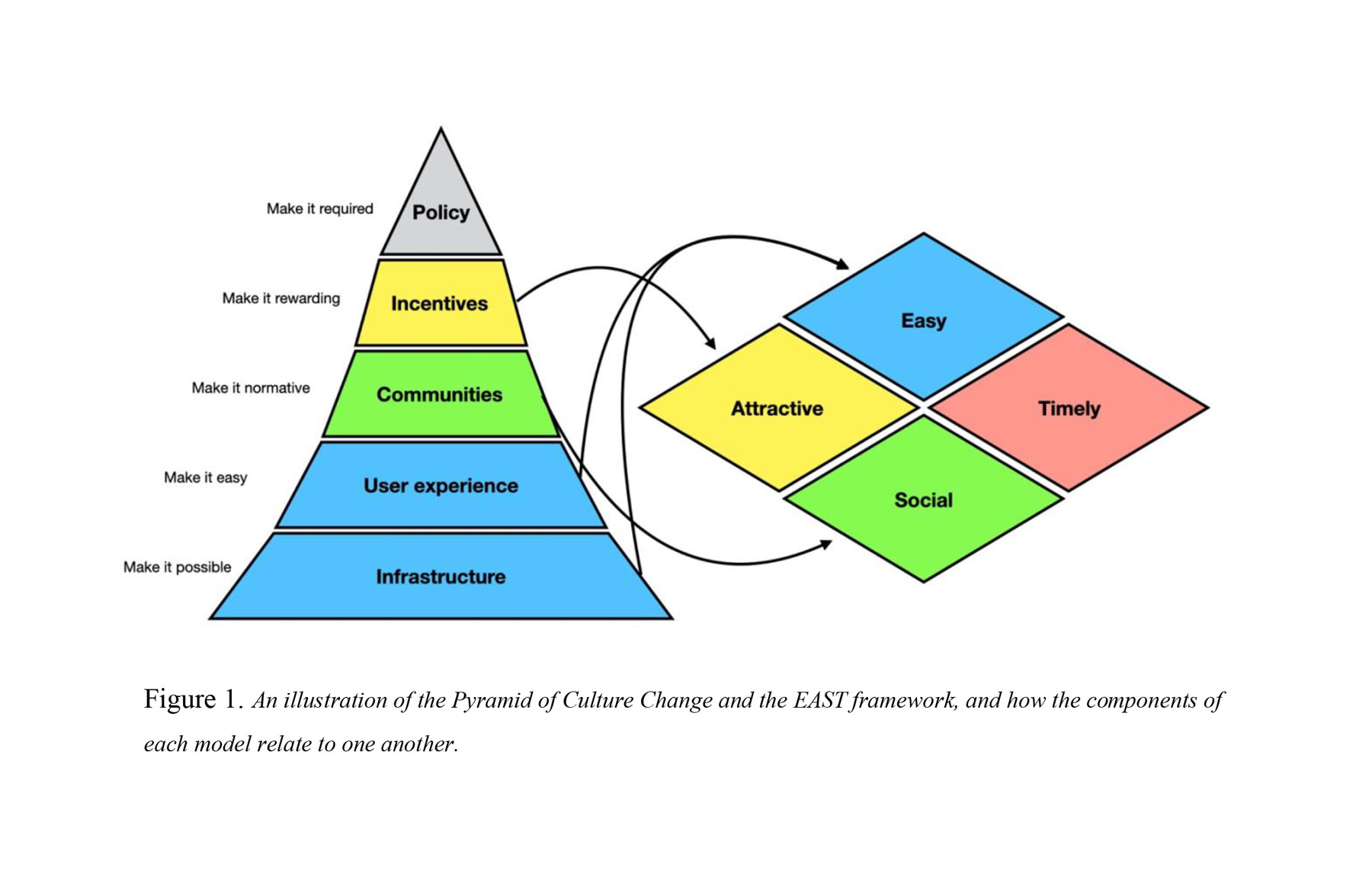

The approach of nudging comes from behavioural research. It maintains that behavioural change can be brought about through gentle nudging, without strict coercion or regulation. Nudging is defined in the report as making “small, easily-to-avoidchanges to a person’s decision-making environment that alter behaviour in predictable ways without forbidding any options or using economic incentives”.

A classic example is the topic of organ donation. In Sweden, for example, everyone is an organ donor by definition. If a person does not want this, he:she must actively object. As a result, the percentage of organ donors in Sweden is much higher than in Germany, where not everyone is an organ donor by law.

Nudging Open Science

Now the group of behavioural scientists has started thinking about how the potential of nudging could be used to further advance Open Science in the scientific ecosystem. Their thesis: Whether researchers and institutions choose to engage in Open Science practices is not necessarily a matter of rational choice. On the contrary: Most decisions are routinely made in the course of emotional, automatic or impulsive processes that are often influenced by psychosocial factors (example: peer pressure). When faced with a decision, a person usually chooses the path of least resistance or least effort. The status quo is maintained.

This also applies to decisions that researchers and institutions make when defining how they conduct, report on, evaluate, publish or fund research (for example, in relation to preregistrations, publishing preprints or Open Data). “Human psychology is at the centre of every decision, whether it be buying toothpaste, running a scientific study, or evaluating a research project”, say the authors. They therefore see great potential in using nudging to improve the use and continuation of Open Science practices. Measures at each of the nodes are essential, to ensure that the changes can really take hold.

The report creates a profile for each of the nodes with its psychology and describes its role in the scientific community. Finally, measures are proposed on how and from whom these seven groups can be nudged towards more Open Science.

Academic libraries node

From the authors´ point of view, two main things prevent comprehensive changes towards more Open Science in libraries: “administrative and financial status quos, and a drive to satisfy customers (students and staff)”. Here, however, one notices that the report is perhaps based on a somewhat outdated image of libraries, as there are many Open Science enthusiasts in modern academic libraries who are driving forward change.

The report further identifies fields in which academic libraries can promote Open Science:

- Create guidelines, training and roadmaps for researchers so they can their research more transparent.

- Subsidise article publication charges for Open Access publications or finance Open Access publications.

- Promote free access to the research generated by the respective institution.

- Advocate FAIR datasets in their own repositories.

- Develop strategies for research data management to ensure that data is recorded, preserved and accessible.

- Establish an online infrastructure that makes it easy for publications to be stored with data and code.

- Open Educational Resources: Libraries can create and make available textbooks, lecture notes, exam papers, videos or other media.

This list is probably not new to staff in academic libraries that are modern and savvy about Open Science, but may encourage them in what they are already doing.

How can academic libraries be nudged?

Broadly speaking, the report highlights two groups of people that can nudge libraries in relation to Open Science practices:

- Students (or other individuals): could contact library staff directly or by email with suggestions on how to implement open practices, according to the report.

- Researchers: when researchers store contributions in library repositories, they can ask how other data, such as preregistrations, preprints or datasets, can be published with their contributions. To highlight the relevance of the associated data, researchers could also offer to coordinate data management workshops. Suggesting Open Access funding initiatives is another area where researchers could become active.

Whether it makes sense and is realistic to expect groups with a very limited time budget (students, researchers) and hardly any incentive, apart from personal commitment, to nudge libraries is open to question. On the other hand, libraries themselves are in many cases committed to actively promoting the cultural change towards Open Access, Open Educational Resources & Co. Perhaps the yawning gap here also stems from the fact that behavioural researchers´ ideas about how modern academic libraries operate are very different from the practice there today?

Conclusion: more Open Science through nudging?

Reflections on how people make decisions and the application of nudging from behavioural science to Open Science is an interesting approach. It causes a change of perspective in observers and causes them to realise their own scope for action and their own “power” to initiate change through behaviour. Basically, the idea is to change the mindset of libraries and other nodes in the academic ecosystem by creating a demand for open practices. The measures and approaches mentioned are neither new nor surprising, but they open up fields of action for particularly committed individuals and individual groups of people.

For readers, or from the perspective of libraries interested in Open Science, a breakdown according to the different groups would have been more helpful, as individuals tend to wonder: What can I do? Nevertheless, nudging in the field of Open Science opens up other options, provided enough users can get excited about nudging the academic node of their choice. Libraries could therefore use the report as an opportunity to systematically apply nudging to promote Open Science.

This might also interest you:

- Robson, Samuel G., Myriam A. Baum, Jennifer L. Beaudry, Julia Beitner, Hilmar Brohmer, Jason Chin, Katarzyna Jasko, et al. 2021. “Nudging Open Science.” PsyArXiv. April 1. doi:10.31234/osf.io/zn7vt.

- Nudging as a political instrument – good intention or state overreach? (German)

- ZBW-Podcast “The Future is Open Science”: FOS 19 Open Science Nudging (German)

This text has been translated from German.

Claudia Sittner studied journalism and languages in Hamburg and London. She was a long time lecturer at the ZBW publication Wirtschaftsdienst – a journal for economic policy, and is now the managing editor of the blog ZBW MediaTalk. She is also a freelance travel blogger (German), speaker and author. She can also be found on LinkedIn, Twitter and Xing.

Portrait: Claudia Sittner©

View Comments

The Openness Profile of Knowledge Exchange: What can Infrastructure Providers do?

How can the scientific incentive system be reformed so that all activities and...