Peter Suber on science in danger: “Host your open and uncensored research in more than one place and preferably more than one country.”

In this interview with Peter Suber, the Senior Advisor on Open Access at Harvard Library and Director of the Harvard Open Access Project at the Berkman Klein Center discusses the current alarming developments taking place in the US research landscape – and offers valuable advice to colleagues from abroad.

The new US administration has changed many things in just a few weeks and turned a few things upside down completely. The academic sector in particular is currently facing significant challenges, with Washington’s influence on individual research projects and the entire scientific process growing daily.

To get a sense of the new developments, which are already having a global impact on research, we spoke with Peter Suber, Senior Advisor on Open Access at Harvard Library, Director of the Harvard Open Access Project at the Berkman Klein Center, and spearhead of the international Open Access movement. Peter has been tracking the impact of Trump administration actions on research, and the news has been coming thick and fast since January 2025.

Peter would like to emphasize that he’s speaking as an individual and not for Harvard University.

Hello Peter! From a European perspective, following the latest news coming from the US research community can be pretty unsettling. From your point of view, what’s changed most significantly since President Trump took office in January?

The major science agencies are now run by people ignorant of science, hostile to it, or ideologically one-sided, and their actions show it. Within days of taking power, they took down thousands of websites, datasets, and research papers in all areas of science. For example, the Department of Agriculture took down climate datasets. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) essentially ended climate research. NOAA even maintains a public list of the climate datasets it plans to delete or discontinue.

The largest science agencies, such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Science Foundation (NSF), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and NOAA, are ordering mass layoffs. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has laid off so many staffers that it can no longer collect data on sickle cell anemia, sexual violence, rates of asthma and abortion, levels of lead in children’s blood, deaths from alcohol, or exposures to hazardous chemicals. Agencies have deleted or orphaned datasets on substance abuse, mental health disorders, adoption, foster care, child welfare, maternal mortality, weather, accidental deaths and injuries, sexually transmitted diseases, greenhouse gas emissions, pollution levels, and deportations.

The Food and Drug Administration has lost 19% of its staff, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) 18%, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 9%. One side-effect is that the CDC will have to stop publishing two open-access journals. Smaller offices face elimination, such as the Global Change Research Program, the EPA Office of Research and Development, the NASA science office, the NOAA Oceanic and Atmospheric Research office, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Institute of Museum and Library Services, and the Institute of Education Sciences. For comprehensive and up-to-date information on the Trump layoffs, I recommend the tracking project at Wikipedia.

Science Protests in March 2025 – Geoff Livingston (CC BY 2.0/Flickr)

Agencies are terminating research grants, sometimes because of their subject matter, such as climate, gender, vaccines, and other topics, sometimes because the grantees are early-career researchers, and sometimes because the recipient institutions have policies that displease the Trump administration, for example on antisemitism or diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). The NSF has terminated more than 500 grants. The NIH has terminated about 800, and was ordered not to tell some recipient institutions “whether the funds are frozen or why.”

When he accepted his party’s nomination in July 2024, Trump promised that “we’re going to get to the cure for cancer and Alzheimer’s and so many other things.” But this month, The Lancet reports that “science and medicine in the USA are being violently dismembered while the world watches.”

Beyond terminating grants already approved, agencies are cutting their budgets for future grants. The NSF could lose two-thirds of its science budget, and NASA half of its.

The NIH is threatening to make drastic cuts to the indirect costs universities can receive for research grants. The Department of Energy is doing the same. These cuts alone could cost research institutions hundreds of millions of dollars a year.

Budget cuts at the Department of Education are forcing the takedown of the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) and its two million open-access documents.

One reason why it’s hard to paint this picture is that so much is happening so quickly. Another reason is that the details change every day. Some of the staff and budget cuts have been threatened but not yet carried out. Others were started but stopped by lawsuits still winding their way through the courts. Others are done deeds.

The official line is that the staff and budget cuts are being done to reduce waste, fraud, and inefficiency. But that’s a pretext for reckless pillaging. Agencies set targets for budget and workforce cuts even before they start looking for waste and fraud. They make the cuts quickly, without time for serious investigation. The cuts are made or suggested by young software developers with no experience in government or forensic accounting. Several agencies fired workers they actually needed, even under new Trump-era criteria, and tried to re-hire them. The Musk-led Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) exaggerates the savings it achieves, does not document it, and changes its mind about what to claim.

One effect of terminating research grants is to increase rather than decrease waste and inefficiency. It can mean the death of laboratory animals, interrupting longitudinal studies before realizing their full value, halting healthcare for patients in clinical trials, dispersing a team that would be hard to reassemble, laying off faculty and staff who would have been the next generation of researchers, and walking away from sunk costs in salaries, equipment, specimens, and reagents. One analysis shows that nearly 40% of cancelled NIH grants “had yet to produce findings, meaning all of the agency’s prior investments won’t benefit the public.” The inefficiency is magnified when the purpose of the terminated research was to increase efficiency.

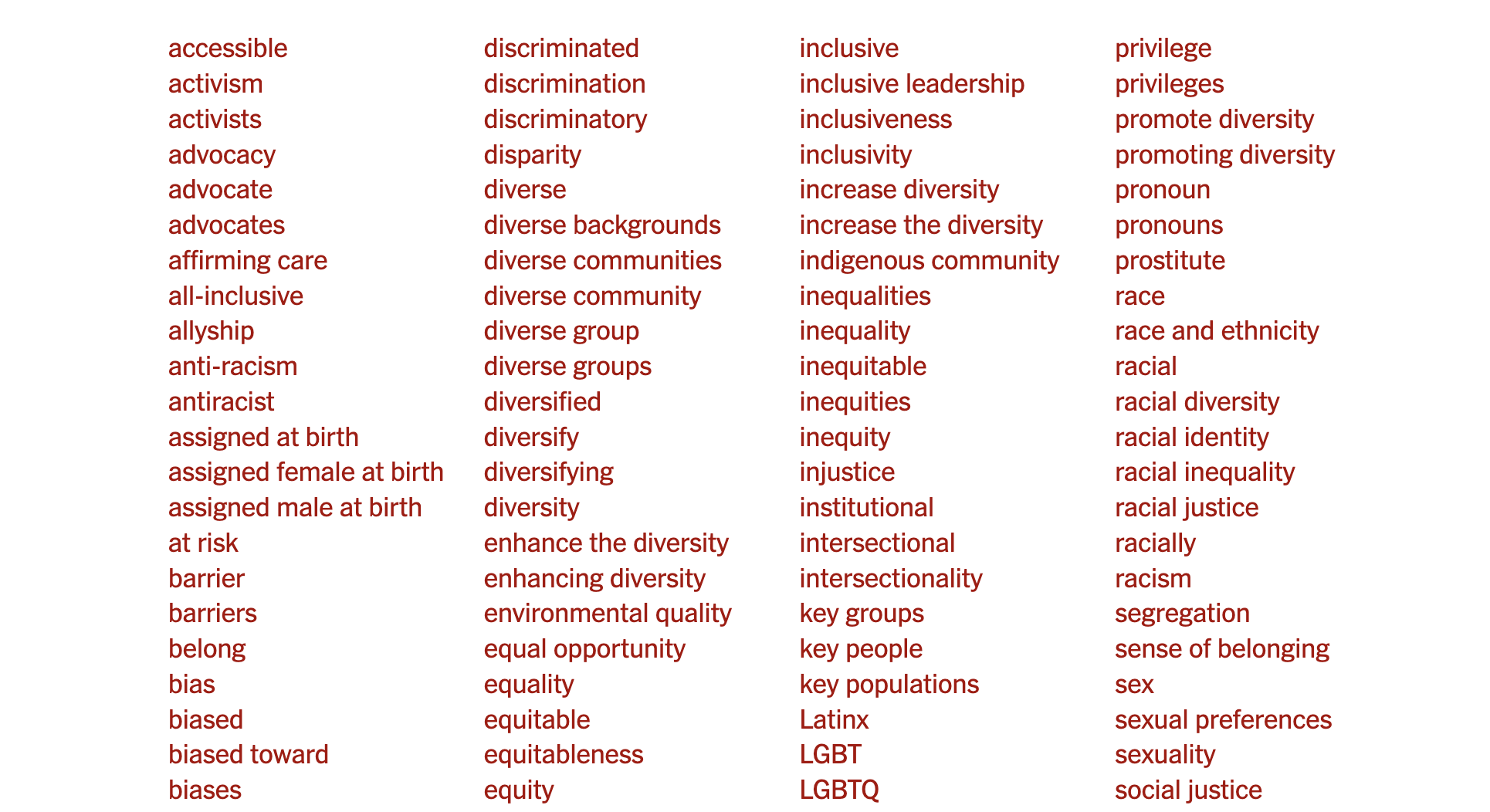

Some of the hundreds of words agencies under Trump have flagged to limit or avoid.

Some agencies have banned words, such as “ethnicity”, “trauma”, and “women”. The Department of Agriculture has its own list, which includes terms like “methane emissions”, “solar energy”, and “clean water”. Many of these terms are unavoidable in honest research on their topics, making the word bans function as topic bans. Government websites have been scrubbed of these words. Use of these words can doom a grant application at the NIH, force a review of research at the NSF, or trigger an agency demand that staff authors retract a journal submission. There’s evidence that Trump officials use these banned words in brainless keyword searches to identify offending content and take it down without careful reading.

Going beyond censorship to fiction and wishful thinking, the EPA plans to revoke its 26-year-old finding that greenhouse gases endanger human health, and replace it with one that justifies relaxed regulations on industry. The Secretary of HHS pledges to find the cause of autism in the next five months and fund studies into the regret that follows gender-affirming surgery. The US Fish and Wildlife Service will redefine “endangered species” so that habitat destruction no longer counts as endangerment. The US Energy Secretary has said that coal “transformed our world and made it better.” Some recipients of climate-related grants have been put on alert that they might be prosecuted for “conspiracy to defraud the United States.”

The Office for Management and Budget (OMB) ordered DOGE to stop using Slack because Slack messages are subject to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. A few days later, the president simply exempted DOGE from FOIA, even though Elon Musk said before the election that “there should be no need for FOIA requests. All government data should be default public for maximum transparency.” Similarly, when Robert F. Kennedy Jr. became Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, he first promised “radical transparency” and then fired the HHS staffers that responded to FOIA requests. As government transparency declines, so does accountability.

More than 1,500 foreign-born students in US universities have had their visas revoked or been deported. Mahmoud Khalil of Columbia had his permanent residency status revoked. Rumeysa Öztürk of Tufts was abducted from a public sidewalk by plainclothes officers in an unmarked car and taken to another state for pre-deportation processing. In each case, the only offense was peaceful advocacy for Palestinian rights. Neither has been charged with a crime.

Science Protests in March 2025 – Geoff Livingston (CC BY 2.0/Flickr)

Noncitizen researchers in the US, including students, are afraid they could lose their permission to stay in the country, especially after an immigration court ruled that they could be deported for their political views. At least one noncitizen researcher retracted a paper on evolution rather than risk deportation. A French researcher was denied entry to the US when border agents searched his phone and found “personal opinions” about Trump science policies. Noncitizen researchers already in the US are reluctant to leave the country, afraid they will not be allowed back in. Researchers from outside the US are reluctant to collaborate with Americans, afraid the funding could be revoked or that they will be targeted for investigation. Ghent University warned its faculty not to collaborate with US institutions. The Canadian Association of University Teachers “strongly recommends” that academics avoid inessential travel to the US. European academics are considering a boycott of US conferences and some are already boycotting.

Non-American researchers who receive US research grants have been required to fill out a lengthy questionnaire about their work. They must affirm that their organization “does not work with entities associated with communist, socialist, or totalitarian parties, or any party that espouses anti-American beliefs” and that it “has not collaborated with…an entity on the terrorism watch list, cartels, narco/human traffickers, organized or groups that promote mass migration.” We know the questionnaire has been used in Australia, the Netherlands, and South Africa.

The termination of grants, cuts to future grant budgets, and caps on grant overhead all entail deep budget cuts for universities. In response, more than a dozen colleges and universities have instituted hiring freezes. Some are already shrinking graduate departments to anticipate lost funds. Students and early career researchers fear that they have no future in the academic world.

The Trump administration has frozen federal grant money to at least seven institutions: Harvard ($2.3 billion), Cornell ($1 billion), Northwestern ($790 million), Brown ($510 million), Columbia ($400 million), Princeton ($210 million), and University of Pennsylvania ($175 million).

On top of these losses, Trump is threatening to tax university endowments. In his first term, he and the Republican Congress instituted the first-ever tax on endowments, at 1.4%. Now he’s threatening to increase it significantly, to 21%. Taking the same idea a step further, he’s also threatening to revoke Harvard’s tax-exempt status.

The campus of Harvard University, located in Cambridge, in the state of Massachusetts, USA. (Kris Snibbe/Harvard University)

Apart from these financial threats, more than 50 universities are under investigation for their DEI policies. At least 60 are under investigation for their antisemitism policies. At one college, faculty members received direct emails from the Trump Equal Employment Opportunity Commission asking Jews to identify themselves.

The next escalation is to remake US higher ed by remaking the criteria for college and university accreditation.

About half of US academics are less likely to recommend their line of work now than before Trump was elected. 75% of surveyed US scientists said they are thinking about leaving the country.

But despite this wide-ranging mix of targeted and reckless damage to US research, Trump has not revoked or weakened the Biden-era directive for all federal research-funding agencies to adopt strong open-access policies. I’m referring to the 2022 memo from the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, often called the Nelson Memo. Not only does the memo still stand, but agencies covered by the memo continue to roll out their OA policies, even under Trump-appointed directors.

On the other hand, Trump officials have removed at least two research papers from a government OA repository. While the authors sue to reverse the decision, Trump has defunded the entire repository — the Patient Safety Network from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Trump has also defunded Knowledge Commons, the repository designated by the National Endowment for the Humanities for its OA content. While the other agency repositories seem unaffected, that could change at any time.

How have researchers, research institutions, and academic libraries been responding to these developments?

Many academics are keeping a low profile and many are speaking out. We should be sympathetic to both groups. There’s a lot to gain and a lot to lose by speaking out, and some people are more vulnerable than others. The risks of speaking out against Trump — or even just speaking in support of Palestinian rights — are especially high for noncitizens on visas, those who have research grants, those who want grants, and early-career researchers looking for positions. We can all point to academics who have lost their funding, their jobs, or their freedom.

Many academic websites are deleting the language of diversity, equity, and inclusion. When we see this, we should understand that retreating from DEI language is not always the same thing as retreating from DEI substance. And like individuals, some organizations are more vulnerable than others.

Columbia University capitulated when threatened with the loss of $400 million in federal funding, and its president resigned soon after. Despite that, Trump escalated his demands against Columbia. When called upon to speak out, some university presidents decline, arguing that it’s more effective to work quietly behind the scenes. A growing segment of this quiet work takes the form of collective action. We don’t know how many institutions are trying this route or how effective it has been. If it’s working even to a small degree, then it’s better than quiet capitulation. But is it working better than unquiet resistance?

Faculty at Rutgers launched a more overt attempt at collective action with their Mutual Defense Compact, which has since been endorsed by faculty at Indiana University, the University of Nebraska at Lincoln, the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, University of Minnesota Twin Cities, the University of Washington, University of Maryland, Michigan State, and Ohio State.

At the same time, and even before Columbia proved that appeasement does not work, several university presidents were speaking out boldly against the Trump demands on universities. I can single out the presidents of Princeton, Brown, Wesleyan, and Mount Holyoke. This trend accelerated when the president of Harvard said no to Trump’s demands. Soon after, more than 500 US college and university presidents signed an open letter to “speak with one voice against the unprecedented government overreach and political interference now endangering American higher education.”

Others are speaking up through lawsuits, more than 200 to date. In court, the plaintiffs are on a winning streak and the Trump administration is losing.

Many people are speaking up on social media, including me. Scholarly societies and other organizations are speaking up through official statements and open letters. Some societies publish individual statements, such as the American Political Science Association, the Association of University Presses, and the Planetary Society, and some release group letters signed by dozens of societies, such as one letter to Congress and another letter to US academics. University faculty are signing letters to their leadership asking them to resist Trump demands and work for collective action, for example, at Virginia, Harvard, Rutgers, California, Yale, and Dartmouth. There are several national or international letters, one, two, three, four, not limited to single institutions.

There are many petitions and open letters to register resistance, call for change, assert principles, and organize action. I’m associated with one to Defend Research Against US Government Censorship.

A handful of journals have spoken up through editorials, for example, BMJ, JAMA, Lancet, Nature, and the American Journal of Public Health.

Some public statements come from within the government itself, such as an open letter from 79 members of Congress, or from government-chartered organizations, such as an open letter from 1,900+ members of the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. There’s even an open letter from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, which is not a government organization but was founded at the same time as the US government by many of the same people, such as John Adams and John Hancock.

Most conspicuously, people are speaking out in public marches and rallies, like Stand Up For Science, Day of Action, Hands Off, Kill the Cuts, and 50501. While only the first two of these focus on research and higher education, academic issues come up in the other protests as well, alongside mainstream issues like tariffs, deportations, reproductive rights, voting rights, free speech rights, social security, medicaid, the rule of law, corruption, Gaza, Greenland, Panama, Canada, and Ukraine.

Most conspicuously, people are speaking out in public marches and rallies, like Stand Up For Science, Day of Action, Hands Off, Kill the Cuts, and 50501. While only the first two of these focus on research and higher education, academic issues come up in the other protests as well, alongside mainstream issues like tariffs, deportations, reproductive rights, voting rights, free speech rights, social security, medicaid, the rule of law, corruption, Gaza, Greenland, Panama, Canada, and Ukraine.

If you’re curious how the academic issues fare with the general public, note the results of recent polling. First, most of Trump’s policies are opposed by most Americans. Second, his academic policies are more widely opposed than any others. The Trump policies most opposed by Americans are expanded federal control over private universities (70%) and cuts to federal funds for medical research (77%).

What specific role can Open Science – especially Open Access and Open Data – play in defending free, neutral, and objective research?

One of the most important actions is to host uncensored, open access research on non-government infrastructure. The US federal OA policies require deposit in agency-designated repositories, which are almost all hosted by the government itself. In better times, that was not a bad idea. But authors with texts, data, or code in those repositories should try to put copies in OA repositories beyond the government’s control, for example, in their university institutional repositories. They should also look for repositories hosted outside the US, like CERN’s Zenodo. Repositories already hosted in the US, could follow the lead of Knowledge Commons and try to create a network of preservation repositories outside the US.

There is a large and growing number of nonprofit, crowdsourced projects to capture government-hosted research and preserve it. I track them in a Mastodon thread, but here I’d like to recognize and thank the Data.gov Archive at Harvard Law School, Data Lumos at the University of Michigan, the Data Rescue Project, the End of Term web archive, the Internet Archive, PANGAEA, the Policy Commons 2025 project, the Preservation of Electronic Government Information project, the Public Environmental Data Partners, the Safeguarding Research project, and the SAFE-Track project.

In some European countries, we’re also starting to see similar pressures emerge, placing increasing stress on science itself. What advice would you give your European colleagues facing these challenges?

Host your open and uncensored research in more than one place and preferably more than one country. Don’t forget that you can work with American universities in this effort, since they have the same interest. Don’t limit it to Europe and the US either, since research organizations around the world have the same interest. There’s a beautiful opportunity here for international community-led cooperation.

Take these steps now or soon, when open research is still within reach for duplication and preservation. Don’t wait until some of it may be censored or deleted.

Some European institutions, like Aix Marseille University and Vrije Universiteit Brussel, are offering research positions to US researchers who feel unsafe or unfree in the US. Norway launched a similar program nationwide, and related initiatives are emerging in Australia, Canada, Denmark, and Germany. These openings are extremely welcome and much appreciated, even if there’s more demand than supply.

Note that Harvard offered a comparable program for Nazi-refugee students in 1938, and has long had large numbers of international students and faculty. But the Trump administration is now threatening to block its admission of international students.

Don’t be afraid to take advantage of the brain drain from the US. First, the US didn’t hesitate to take advantage of the brain drain from German-occupied Europe in the mid-20th century. Second, this benefited the new host country as well as those who found refuge here, including scientists like Albert Einstein, Leo Szilard, and John von Neumann, and non-scientists like Hannah Arendt, Thomas Mann, and Billy Wilder. Finally, of course, research is international, and we should work around spasmodic outbreaks of nationalism by helping researchers find support and hospitality in other countries.

Peter, thank you so much for this interview!

(The interview was conducted by André Vatter, ZBW Open Science Transfer)

Peter Suber is an American philosopher specializing in the philosophy of law and open access to knowledge. He is Senior Advisor on Open Access (in Harvard Library) and Director of the Harvard Open Access Project (in the Berkman Klein Center). Find out more about him on his website and follow him on Mastodon and BlueSky.

View Comments

AI Inspirations for Libraries: From Study Bots to Conversations with Books

What do Collegebot, Hello Literature and Book.AI have in common? They are all AI...