Study on Twitter Usage: What Roles Do Academic Hierarchies Play?

What are the motivations behind the use of Twitter, and what roles do hierarchies play in academia? An interdisciplinary study of more than 1,400 Twitter users from the world of computer science provides some indications. We interviewed the author of the study about her approach and the results.

In the following,  Dr Stephanie B. Linek, academic at the ZBW Leibniz Information Centre for Economics and lead author of the study “It’s All About Information? The Following Behaviour of Professors and PhD Students in Computer Science on Twitter”, provides a few details.

Dr Stephanie B. Linek, academic at the ZBW Leibniz Information Centre for Economics and lead author of the study “It’s All About Information? The Following Behaviour of Professors and PhD Students in Computer Science on Twitter”, provides a few details.

You have investigated the reasons academics have for following each other on Twitter. How did you come up with the idea of exploring this topic?

The idea was developed during the “Netiquette and Profile in Science 2.0 research project“, which deals with forms of interaction, communication and self-representation of researchers in the social web. For researchers, there is the problem that social media can be used both privately and academically, so that social roles (as a private individual and as a researcher) can become confused. In this respect, we were interested in finding out which motivations are linked with the various ways in which social media are used. The microblogging service Twitter was especially interesting for us, because – unlike social networks such as Facebook – various kinds of user relations are possible, i.e. one-sided following or mutual following. Since our project was highly interdisciplinary, we were able to examine these relations via both social science and computer science methods, giving us new options for analysis.

What exactly did you investigate in your study?

The study focused on the use of Twitter by computer scientists. On the one hand, we wanted to know whether the academic use of Twitter was actually motivated solely by the search for information. On the other, we also wanted to analyse the extent to which the academic hierarchy of account holders and followers had an impact on following behaviour – whether, for example, professors are followed as an act of courtesy. In order to look into these questions, we analysed not only the quantity of information, i.e. the number of tweets from an account, but also the subjectively perceived quality of information. We did the latter by also considering the academic level of the account owner as a (subjective) indicator of academic expertise. With the help of variance-analytical methods, it was possible for us to use hypotheses to test the extent to which information-gaining motivations are prevalent, or whether career-planning factors also play a role.

How is Twitter used by the researchers who were investigated in this study? Which motivations play a central role?

The information-gaining motivation is in fact quite central to computer scientists’ use of Twitter.

In addition, career planning also affects following behaviour on Twitter.

This is particularly evident in the form of strategic courtesy effects: Twitter accounts of professors have a relatively high number of academic followers even when they demonstrate inactivity. This cannot be explained by the quantity or subjectively perceived quality of information alone. In addition, our data also contain indications of peer networking among professors. This means that professors are networking and following each other. Interestingly, this was not demonstrated amongst PhD students.

What methods did you use to determine the role of academic hierarchies in the use of Twitter?

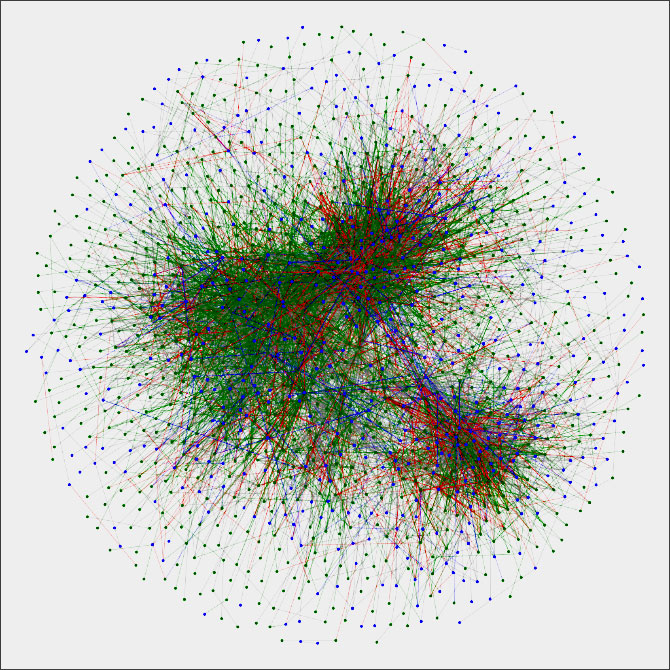

This question is, so to speak, the core of our interdisciplinary collaboration. As we analysed a very large data set (from over 1,400 computer scientists on Twitter), two essential steps were needed to examine the influence of academic hierarchies. First of all, the Twitter profiles had to be analysed using computer-scientific methods so that we could obtain the necessary information on academic hierarchies. (Manual analysis of the profiles is difficult to achieve with such a large data set). We then had to analyse the resulting data set using variance-analytical statistical methods from the social sciences so that we could differentiate the information-gaining motivation, courtesy effects and other motivations on the basis of the pure usage data.

Your research project is interdisciplinary. How did you organise this interdisciplinary work?

The general content coordination and work scheduling mostly took place via group Skype sessions. The actual individual work stages were often coordinated in a two-party conversation or via email. For data processing and data analysis in particular, close reciprocal controls were necessary. It was often a real challenge to coordinate the various approaches from psychology, communication studies, and computer science. In addition, the various locations and the availability of the individual partners had to be taken into account. Yet all in all, the interdisciplinary cooperation has proven to be very fruitful. One discipline alone could not have carried out the investigation in this form.

In your view, which research questions remain open?

So far, we have only investigated computer scientists on Twitter. To this extent, it is of course interesting to see whether the results can also be reproduced in other disciplines, especially in disciplines with a higher percentage of women and a less technological orientation. In addition, this study was based on pure behavioural data and on usage data. Expanding on this, we are currently evaluating a further questionnaire-based study on subjective views.

A further open research question for future investigations concerns the temporal development of following behaviour, especially with regard to mutual following. The question of unfollowing, and when and how often it happens, will be an important part of future studies.

Another interesting question is the extent to which the open science movement will change the influence of academic hierarchies and usage motivations in the future – whether researchers who, for example, show a higher affinity for the open science movement also demonstrate different academic usage behaviour with respect to social media.

Additional information:

- It’s All About Information? The Following Behaviour of Professors and PhD Students in Computer Science on Twitter

- Further blog post on this topic: New media, familiar dynamics: academic hierarchies influence academics’ following behaviour on Twitter

Making Open Educational Resources Locatable: The OER-Hörnchen Search Tool

Everyone is talking about Open Educational Resources (OER) at the moment. However, it...